Restoration of Extinct Species

Our ancient ancestors told stories of great prehistoric beasts in the form of drawings on the walls of caves. These animals played a significant role in their daily lives, and they clearly felt their stories were worth telling. And whether they realized it or not, the stories themselves would long outlive those who wrote them. So, in effect, they’ve been able to tell those stories to us thousands of years later.

All Images © A. James Gustafson

Simbakubwa comparison. African Lion (Panther leo) and reconstructed Simbakubwa kutokaafrika. Colored pencil and ink. ©2020 A. James Gustafson

I’ve always been drawn (no pun intended) to art that informs. When I made the choice to pursue art as a career, it was clear to me that the most fulfilling path would be one that allowed me to combine my creative passion with my love of both learning and teaching. I chose a path that would afford me the opportunity to immerse myself in and make contributions to the worlds of science and natural history. It was a chance for me to utilize the talents that I have been given (and have spent a lifetime cultivating) to teach others what I have learned and hopefully instill that same passion in someone else. While my portfolio consists of a wide range of subject matter including everything from biology and natural conservation to medical illustration—prehistoric restoration is without question my greatest artistic passion. And it is in this pursuit that my work has garnered more of a response from viewers than perhaps anything else I do.

New avenues such as social media have provided artists of every stripe with a new and unique opportunity to share their work with a larger audience than ever before. Platforms such as Instagram have allowed me to do the same, all while engaging with followers and social media users— answering questions, participating in discussions, and even spirited debates. There is truly no greater sense of satisfaction for me than when someone says something to the effect of “I had never even heard of this species until now,” or “wow, just imagine how beautiful this animal must have been!” Or, “I want to learn more about this.” These are the moments where I feel I have truly served my purpose as a natural history illustrator. Just as important, however, are the interactions in which someone will push back against my work, question the science behind my choices, or just flat-out refute the accuracy of a particular piece. It is in these moments that I’m able to put my own work to the test, and ultimately prove whether or not it can stand up to the rigors of scientific scrutiny. I am often asked about the process behind creating an illustrated reconstruction of an animal that neither I, nor anyone else, have ever seen in the flesh. However, that process is typically a little more involved than can be summarized within the comment section of a social media post or articulated in 280 characters or less.

I tend to approach restoration much as a portrait artist would. But as you might imagine, the biggest difference lies in the fact that a portrait artist has the luxury of having his or her subject sit for them, or at the very least has access to photographic references of the subject from which to draw. Neither of these are luxuries afforded to a paleoartist.

Unlike our ancestors, these animals are no longer a part of our daily lives. Quite simply, our subjects are long gone. A good majority of them lived thousands, if not millions of years before the advent of cameras, and sadly man has yet to invent time travel. So, with first-hand viewing not being an option, my initial priority is to create a visual reference of my subject using whatever concrete, scientific evidence is at my disposal, combined with a knowledge of today’s living animals. This part of the process begins with research. Lots and lots of research.

The research process typically begins by consulting the fossil record. Fossilized remains give us the most clues as to what an extinct species may have looked like. Aside from informing us of the animal’s classification, be it mammal, reptile, bird, etc.—they also tell us about the animal’s basic structure, how it was built, and how it may have moved. It goes without saying that a more complete fossil record lends itself to a more complete understanding of a given species. However, at times, an extinct animal’s very existence might be known only from one or two isolated bones, or a portion of its dentition. A few years ago, I was given the task of reconstructing a recently described human ancestor of the late Miocene, for whom the only known evidence is a small section of jawbone and a few scattered teeth. I, of course, informed the author who commissioned the work that the result would be largely speculative. In fact, one professor of anthropology I consulted with essentially told me not to even bother. But, as was my charge, bother I did. Both my collaborator and I were happy with the outcome from an aesthetic standpoint, but if pressed, I wouldn’t necessarily defend its scientific merits with the full extent of my conviction.

With regards to reconstructing animals for which there are vast amounts of evidence, whenever possible, I prefer to have actual specimens in my hand to observe. This allows me to study them, take measurements, and record observations about any noteworthy features they may display. When this isn't possible, the internet becomes an invaluable tool. There is a wealth of photographic information available online. Several universities and other educational institutions often make databases of their collections available to the public.

While I try to collect as much fossil evidence as possible, bones only tell a portion of the story. They give you a general idea of an animal’s physical form, but there will always be things that a skeleton can't tell you. Take, for example, the elephant. Let's pretend for a moment that you had never seen an elephant. If I were to show you a photograph of an elephant's skeleton and asked you to draw what you think that animal may have looked like, it is highly unlikely that the final result would truly resemble what an elephant looks like in life. How would you know to include a long trunk where a more common nose would usually appear? Would you observe anything about its skull to indicate large, floppy ears? Being that an elephant is a mammal, you may even be inclined to cover it in fur. As the saying goes, “you can’t know what you don’t know.” And so, once I have gathered a sufficient amount of skeletal references, the research process moves on to hunting for clues elsewhere.

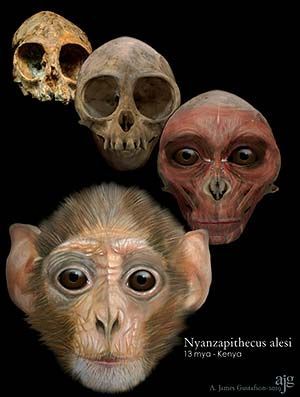

Ape facial reconstruction (Nyanzapithecusalesi). Adobe Photoshop, colored pencil, and ink. ©2019 A. James Gustafson. Original photo: Fred Spoor.

In order to get a fuller picture of what a prehistoric creature may have looked like, I want to learn as much about it as I can, beyond the physical. I want to know when it lived, where it lived, and how it lived. What was its environment like? What was the climate like? What did it eat? Did it hunt? Was it hunted? Does it have any living relatives? If not, does it share any common ancestors with any animals of today? All of this information is useful in the restoration process because the answers to these and other questions all play a role in how animals look and why they look that way. An animal’s physical appearance is the result of countless adaptations it has evolved over the course of eras and eons. In nature, physical form usually serves a practical function. A zebra’s stripes help to make it easily identifiable to other zebras, but it also aids in body temperature regulation. A male lion’s mane never stops growing and becomes darker with age. Territorial by nature, his thick, black headdress broadcasts to potential mates that he is a survivor and excels at defending what is his. It’s these understandings and the inclusion of these types of details that, while never undeniable proof of accuracy, can lend credibility to the educated guesses behind an artist’s hypotheses.

Many of the reconstructions I illustrate are commissioned by authors, publishers, or researchers. But still, there are examples in my portfolio that are self-initiated. These tend to be projects pertaining to subject matter about which I am most fascinated; central among those being human evolution. In 2017, findings were published about a 13-million year- old infant ape skull unearthed in Kenya. It belonged to a previously unknown species named Nyanzapithecus alesi, and was discovered by a team led by Dr. Isaiah Nengo of Stony Brook University and the Leakey Foundation. A fine illustrated rendering of Nyanzapithecus alesi accompanied the findings in all of the major publications of the day. However, intrigued by this discovery, I felt inclined to try my hand at my own, independent work on the subject. As a relatively unknown illustrator (as I admittedly was at the time, and perhaps only slightly less known than I am today), one seldom knows whether a discovering scientist would or would not agree with the science behind your reconstruction.

But in 2019, I was fortunate enough to find out when I was contacted by Dr. Nengo himself. He had come across my work and was kind enough to reach out to let me know that he was pleased with it. So much so, that he asked to use my reconstruction in his lectures on the subject. It is my hope that this validation is a testament to the careful process by which I went about rendering this particular species.

A Nyanzapithecus alesi skull, about the size of a lemon, had been catalogued with 360, three-dimensional images. I began by using these images, along with those of modern-day apes, to create a photographic composite model of the complete, intact skull as it may have appeared in life. From there, I reconstructed the musculature and fleshed out the face of a two-year-old primate, using proportions and features seen in juvenile Old World monkeys and gibbons—thought to be their closest living relatives. I believe the result is an image that allows the viewer to gaze into the eyes of an animal that is relatable, which is one of my ultimate goals when approaching any reconstruction.

I have found that prehistoric animals have a way of becoming almost like mythological creatures. Many of them lived in a time that is so distant from I have found that prehistoric animals have a way of becoming almost like mythological creatures our own, that it's easy to lose sight of the fact that these were living, breathing beings. Many of the restorations I saw during my childhood years seemed generic, almost lifeless. I found it difficult to imagine myself standing before the animals depicted in the books and magazines that I spent time poring over. Today, one of my main foci—apart from creating a depiction that adheres as closely to the available evidence as possible—is to challenge viewers’ preconceptions of what they believe they already know about the animals of times gone by.

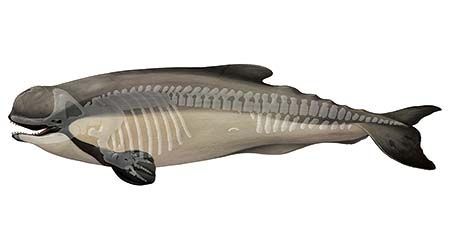

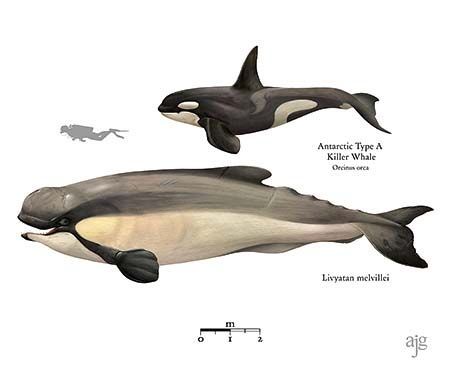

As an example, I recently undertook a reconstruction of the extinct whale, Livyatan melvillei. Many wonderful reconstructions of this great beast have been done. I usually tend to shy away from retracing ground that has been so aptly covered, but there was an angle that I had not previously seen represented in other Livyatan melvillei restorations. As a general rule, I do my best not to let existing work influence my own.

Above: Livyatan skeletal. Adobe Photoshop, colored pencil, and ink. ©2019 A. James Gustafson. Below: Livyatan comparison. Colored pencil and ink. ©2020 A. James Gustafson.

Livyatan melvillei is a distant relative of the modern-day sperm whale. Accordingly, most reconstructions depict him as such. But when I would look at the skull, something much different would come to mind. And so, I set out to reconstruct this ancient cetacean, not as a colorless, vaguely sperm whale–shaped monster reminiscent of Moby Dick himself. Instead, using what I know of the similar skull features exhibited in modern-day orcas and pilot whales, such as the size and shape of the maxillae and supracranial basin, my aim was to create an animal that offers the viewer a slightly different perspective, while not deviating from all that is widely accepted as fact. Because of this, I sought to straddle the line between sperm whales and a more delphinian body shape and markings, blending those physical attributes with that of Pygmy and Dwarf sperm whales—such as the presence of caudal humps and a low-profile dorsal fin. Reaction to my interpretation was mixed, but I was pleasantly surprised to find that most, including some well-known paleontologists specializing in the study of prehistoric cetaceans, were appreciative of my take on this legendary marine mammal.

At times, deviating from what is commonly accepted as the prototypical representation of a prehistoric species can be met with skepticism, even antipathy. This notion underscores the importance of strict adherence to concrete science. I base my reconstructions solely on what is available to me in the form of evidentiary proof. However, illustrations do require artistic choices. But I believe that as a natural history illustrator, it is imperative that making choices does not cross over into taking liberties.

The restoration in my portfolio that has garnered more reaction than any other is an illustration I did in 2020 of

Simbakubwa kutokaafrika

(first Image in this article). If you’re not acquainted with this species, you’re not alone. I discovered through sharing my illustration online that most of my audience was unfamiliar with this Miocene Hyaenodont. A paper describing this African carnivore had only been published about a year prior, after a paleontologist working at the Nairobi National Museum happened upon a previously unidentified mandible in the depths of the museum’s collections. The accompanying artwork was crafted by the incomparable Mauricio Anton, and elegantly depicted the terrestrial predator—quite possibly the largest ever—in his natural surroundings. But as paleoartists are often wont to do, I couldn’t resist the urge to add an original restoration of

Simbakubwa kutokaafrika to my own portfolio.

Simbakubwa skull reconstruction. Adobe Photoshop. 2020 A. James Gustafson. Original photo: Matthew Borths.

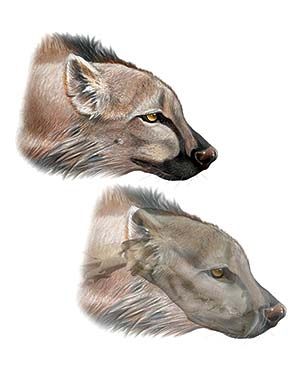

I intended to produce an illustrated study that compared him to Africa’s modern-day apex predator, the lion; an animal from which the name of Simbakubwa kutokaafrika is derived but shares no familial relation. And, as is my practice, I began by disregarding existing artistic interpretations and started from scratch. I studied the photos and writings describing the known fossil specimens, which are scant to say the least. And, much as I did when tackling Nyanzapithecus alesi, I sought to first reconstruct the skull using the existing mandible and partial maxilla as a guide. Determining the proportions and overall size was a bit more complex, as there are very few known postcranial remains. I arrived at his scale by comparing my skull model and the existing calcaneum (heel bone) to that of other Hyaenodonts as well as their extinct and extant descendants. I worked on my restoration of Simbakubwa kutokaafrika, on and off, for the better part of a year. I went through several rough drafts. Again, I wanted a final reconstruction that was relatable; one that took cues from that which would be familiar to the viewer, but still represented something unique.

When we look at the apex predators of today—lions, tigers, orcas, and even the emblematic bald eagle— they each have a distinct, striking appearance that is exclusive to them. And so, I believe it is logical to deduce that Simbakubwa kutokaafrika would have as well. The final illustration (first image in this article) depicts a skulking animal, ears back, and head lowered— perhaps stalking distant prey or warily approaching a potential rival. He sports a dark, wiry mane running down the length of his back that, when fully grown, will not only advertise his virility, but also protect his neck and throat during inevitable battles for dominance and supremacy among his own kind. His short fur is emblazoned with faint stripes and spots at the legs, neck, head, and tail, helping to break up his shape in the spotty forests in which he may have hunted. His steady, piercing eyes are shown leering from behind a black mask designed to shield his vision from the glaring African sun. Speaking frankly, I’m proud of the final result. And as I mentioned, it received quite a response once I did finally share it for public consumption. Much of that response has been positive. Some of it has been skeptical. But it has since been talked about, shared, “liked,” and “disliked” more times than I can count. But what matters most to me is that it has started conversations. It has introduced this largely unknown animal to people who might have otherwise never learned of it.

Simbakubwa head reconstruction. Adobe Photoshop, colored pencil, and ink. ©2020 A. James Gustafson

As I’ve stated time and again, that is my goal. Sharing what I learn, through the abilities that I have. In fact, that is really the goal of all scientific communication. But unlike other scientific art forms, the aim of prehistoric restoration is to reintroduce creatures, big and small, that once inhabited the landscapes of our world and now occupy the landscapes of our imagination. The challenge exists in doing so while maintaining a balance between what I can imagine and what I can prove. My job is to help tell their stories. And my responsibility is to tell them as accurately as I can. Because much like our ancient ancestors, I believe theirs are stories are worth telling.

This article appears in the Journal of Natural Science Illustrators, Vol. 53, No. 3, 2021

Share this post: