Client Best Practices

Guidelines for commissioning professional natural science illustration

image credit: Travis Vermilye (member since 2010)

Working with a professional science illustrator helps ensure that your visual materials are accurate, effective, and visually engaging.

These guidelines are designed to help clients (whether individuals, publishers, institutions, or research teams) collaborate successfully with illustrators in natural science communication.

Find an Illustrator to collaborate with, in our Professional Gallery

1. Define the Project

Be clear and specific about your needs.

Before reaching out, outline your project goals, intended audience, and how the artwork will be used (e.g., journal publication, exhibit, website, educational materials). Include:

- Project description and scope (number of illustrations, level of detail, color or black & white, etc.)

- Final format and usage (digital, print, merchandise, etc.)

- Target audience and purpose (educational, commercial, scientific, etc.)

Why choose illustration over photography?

While photos and imaging systems can capture detail, they don’t always engage or clarify. Illustrations, on the other hand, focus attention, simplify complexity, and highlight what’s most important.

An artist can combine accuracy with storytelling, creating visuals that feel both human and memorable.

Why work with a visual science communicator?

Visual science communicators specialize in translating complex information into visuals that are accurate, engaging, and tailored to your audience.

We’re often too close to our own work to communicate it effectively - a skilled communicator can step back, identify your core message, and craft visuals that tell your story clearly. It’s an investment that helps your research reach and resonate with wider audiences.

Important questions to ask before beginning

Do you need science graphics but are unsure where to start? Ask these three questions to help in defining the project scope before contacting a Visual Science Communicator:

1. What?

What is the most important information or part of your project that needs to be shared? What specific and important details need to be included? If you're not sure how many and what kind of graphics you need, communicating the most important characteristics of your project that needs to be shared can help

2. Who?

Who will be the audience of your work? There are numerous different audiences and demographics of scientific visuals such as other researchers and scientists, the general public, internal stakeholders, etc. and narrowing down on this is very important. Make sure to communicate who your audience is when approaching an illustrator for your project.

3. Where?

Knowing where the work will be used is crucial in determining the project cost.

image credit: Sophia Hart

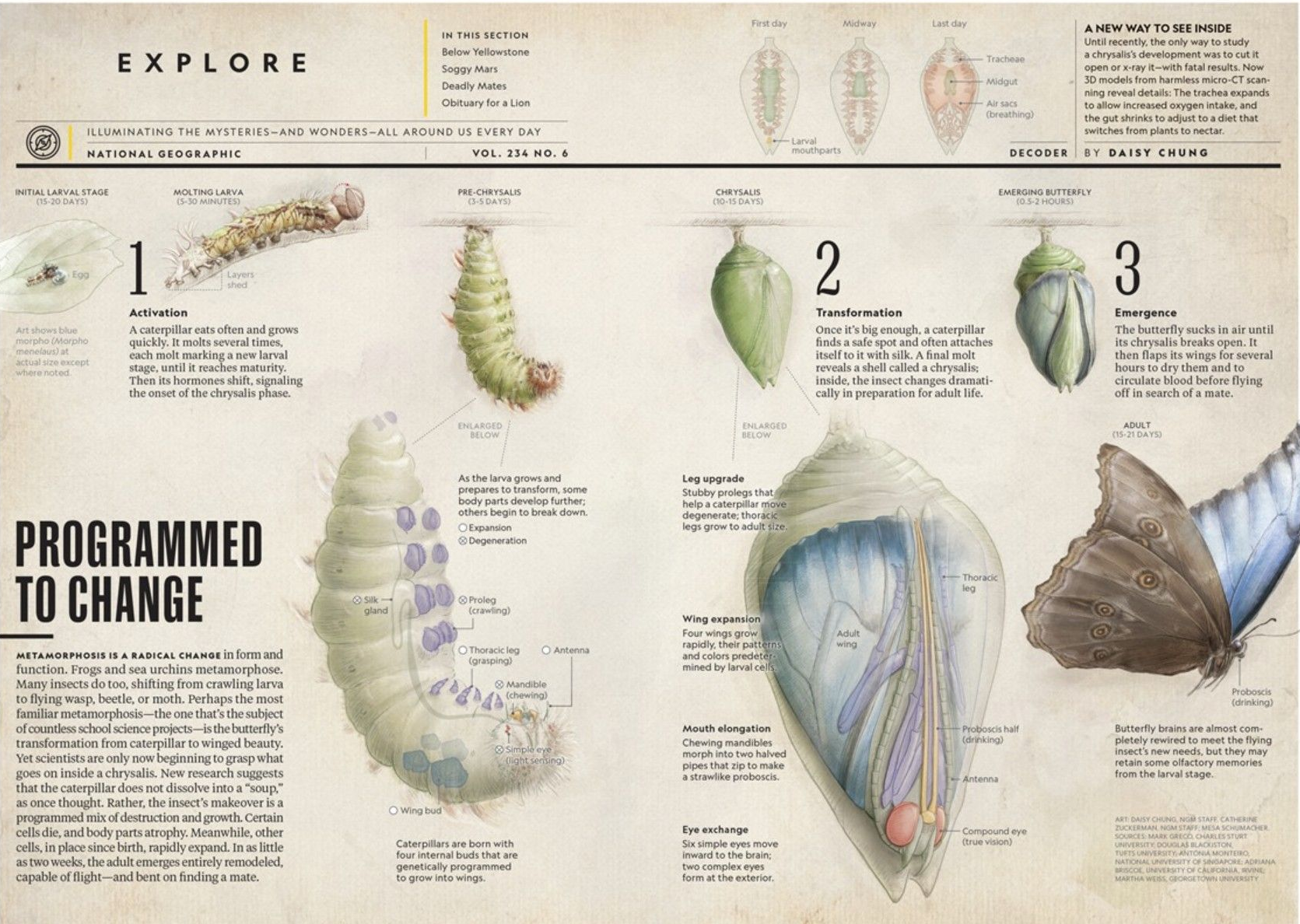

image credit: Daisy Chung

Accurate, well-organized reference materials help ensure scientific precision.

Make sure to prepare these materials in advance and provide them in early communications:

- Reference photos, diagrams, or samples (with usage rights confirmed)

- Accurate captions, specimen data, or field notes

- Contact information for subject-matter experts (if needed)

The more accurate your references, the more faithfully the illustrator can represent the subject.

Example reference materials:

Written Materials

- Research papers, abstracts, or reports relevant to the subject

- Captions, labels, or figure text that will accompany the illustration

- Descriptions of the intended message, audience, and visual tone (e.g., educational, editorial, exhibit-style)

Visual References

- Clear, labeled photographs of specimens, anatomy, field sites, or instruments

- Microscopy or imaging data (CT scans, SEM images, etc.) with interpretation notes

- Sketches, diagrams, or previous figures that show what you’re envisioning - even rough ones help!

- Maps or location data (if applicable to species or habitats)

Scientific Context

- Species names, taxonomic details, or anatomy keys

- Scale references (e.g., specimen size or magnification level)

- Comparative images to clarify differences between species, stages, or features

2. Provide Reference Materials

Plan ahead and maintain regular communication.

Quality illustration takes time, especially for complex scientific subjects. Reach out to illustrators early to allow for research, sketch review, and revisions.

- A typical project lead time: anywhere from 4–12 weeks depending on scope

- Be prepared to respond promptly to questions and milestone updates

- Build in review periods for feedback and approval. Reviewing and providing feedback at any stage can take a week or even longer in some cases - especially if multiple people are involved. Consider this when determining the lead time you will need, and keep it in mind during the project so your illustrator can stay on deadline.

3. Timeline and Communication

image credit: Jennifer Landin

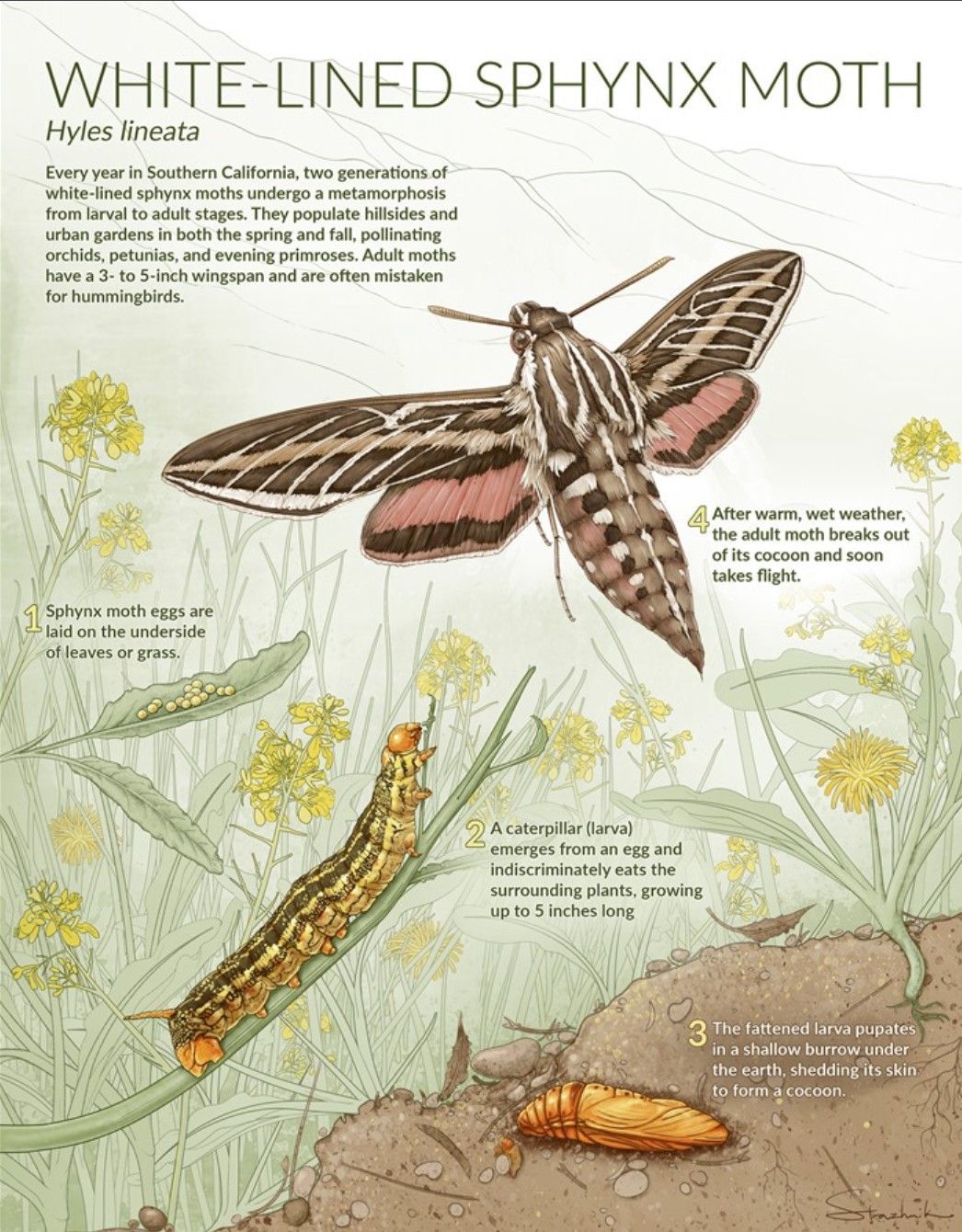

image credit: Inna-Marie Strazhnik

It is always advisable to work with a written agreement.

A contract protects both the client and the artist by clearly defining:

- Scope of work and deliverables

- Timeline and payment schedule

- Usage rights and limitations

- Revisions and approval process

4. Contracts and Agreements

Illustrators typically retain the copyright to their artwork.

Clients are most often granted a license to use the image for agreed-upon purposes. Before expanding usage beyond the original agreement (e.g., new publications, merchandise, marketing), always request additional permission and negotiate new terms.

Who is the author of a science graphic?

Who is an author?

Under the copyright law, the creator of the original expression in a work is its author. The author is also the owner of copyright unless there is a written agreement by which the author assigns the copyright to another person or entity, such as a publisher.

An idea itself can't be copyrighted; the copyright applies to the tangible product that is created. When a graphic image is created (pictoral work) it becomes the tangible product brought about by the labor, skills and expertise of the artist (aka author).

The owner of copyright in a work has the exclusive right to make copies, prepare derivative works, sell or distribute copies, and display the work publicly. Anyone else wishing to use the work in these ways must have the permission of the author or someone who has derived rights through the author.

5. Copyright, Ownership, and Usage Rights

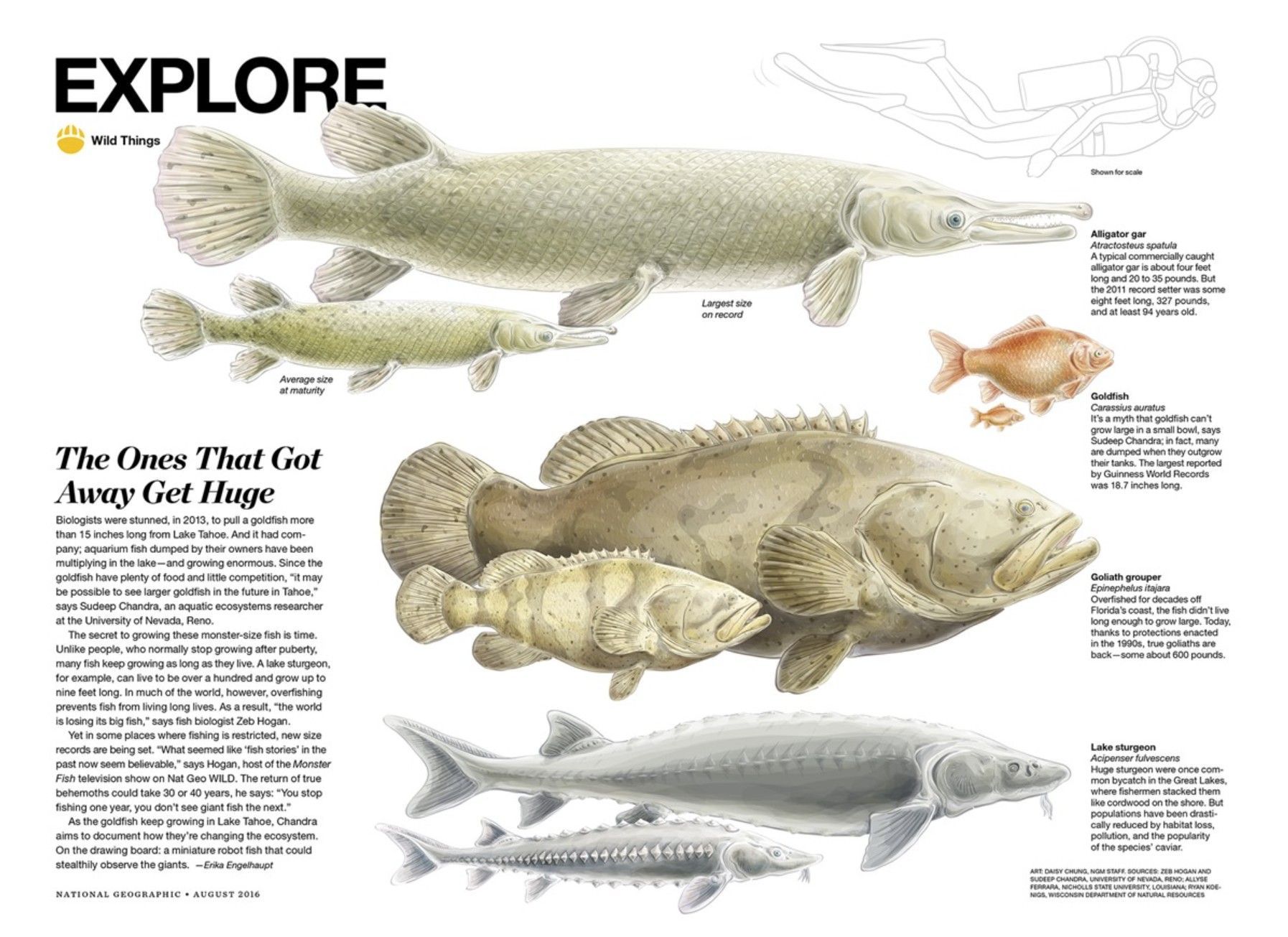

image credit: Daisy Chung

6. Credit and Acknowledgement

Always credit the illustrator when artwork is published or displayed.

Include the artist’s name in captions, credits, or acknowledgments according to the publication’s format. This recognition supports professional transparency and the illustrator’s career.

Example credit line: Illustration © [Artist Name], used with permission.

image credit: Jillian Ditner

Good collaborations are built on respect, trust, and clear communication.

- Provide constructive feedback on sketches and drafts

- Respect the artist’s creative process and professional expertise

- Keep records of contracts, correspondence, and usage rights for future reference

Establishing an ongoing working relationship with a trusted illustrator can streamline future projects.

7. Maintaining a Professional Relationship

Ready to connect with a professional science illustrator?

image credit: Carol Schwartz