Member Spotlight: Dino Pulerà

I’ve always been inquisitive and fascinated by nature. I would spend many hours drawing as a child but, despite my interest in nature, I never thought to draw it.

Dino Pulerà

I’ve always been inquisitive and fascinated by nature. I would spend many hours drawing as a child but, despite my interest in nature, I never thought to draw it. Instead, I spent my time reading and drawing Marvel Comics superheroes. Being the son of immigrant parents, I was encouraged to pursue a career that was stable and with a steady income; they didn’t want their son to become a struggling artist. So I set my sights on science with the hopes of going to medical school.

In my senior year in high school, my biology teacher noticed that I used drawings to record my observations in labs and mentioned that some people made a living from illustrating scientific concepts. Looking back now I’m shocked that I didn’t even consider a career in scientific illustration. I guess I thought since this vocation involved art, it would be a hard sell to my parents. So I put it out of my mind.

After my first two years of university, I realized that I didn’t understand organic chemistry, a requirement for med school, despite my two attempts at the subject. With this crushing realization before me, I had no idea what to do with my life. I always told myself, if worse comes to worse, I can always teach — but that would be a very last resort.

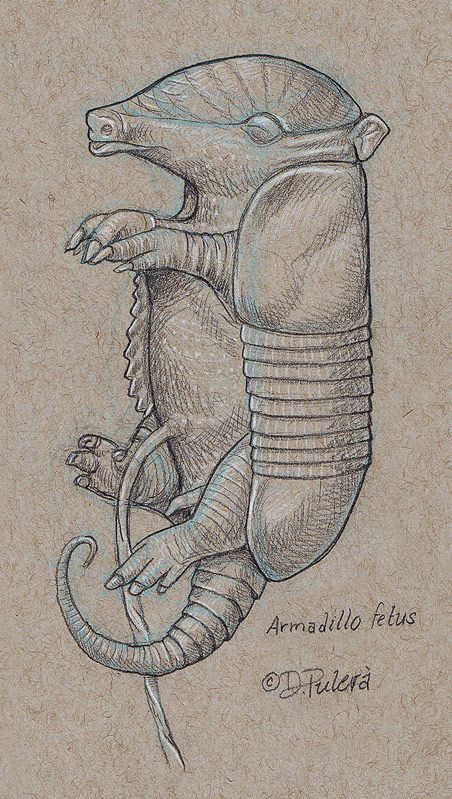

Armadillo fetus study: graphite pencil on toned paper with coloured white pencil highlights.

Throughout my undergrad time at the University of Toronto, I noticed little posters in the medical sciences building about an open house for the Department of Art as Applied to Medicine, now called Biomedical Communications (BMC). These little posters always had amazing illustrations which captivated me. For fun I went to a couple of these open houses: I was blown away by what I saw. I couldn’t believe the caliber of work depicted in a variety of media and such diverse topics ranging from food webs to human surgery to drug interactions to gross anatomy. I was quite envious of these students and wished I had their talent. But even then, I still never considered a career in scientific illustration because I only drew for fun, which wasn’t much anymore because I never could seem to find the time or a reason.

Armadillo fetus study: graphite pencil on toned paper with colored white pencil highlights. © Dino Pulerà

When I completed my undergraduate degree in zoology I still had no idea of what I wanted to do. I decided I would take some time off and figure out some options. I decided to prepare for a career in teaching. For the next two years, I volunteered my time at an elementary school to gain experience. I also took undergrad courses for general interest and to increase my GPA. The courses I took included in vertebrate paleontology, comparative vertebrate anatomy (CVA) and intro to paleontology, because I was also entertaining the idea of possible graduate studies in paleontology. I volunteered and later worked for the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) in the vertebrate paleontology lab preparing and repairing fossils, molding, and casting, and also helping to mount a Triceratops skeleton. During this time, I thought it would be fun to draw again and coincidently discovered some non-credit scientific illustration courses. These courses were taught by GNSI member Celia Godkin, an instructor at the BMC program. I absolutely loved these courses! After completing the third and final course, I asked Celia if she taught any more courses. She disappointingly told me that she didn’t, but encouraged me to apply to the BMC program. I was utterly shocked by her suggestion: I tried to explain that I had no formal art training and quite frankly didn’t think I was qualified. She disagreed and encouraged me to apply and also offered to write a letter of reference. I couldn’t contain my excitement and hope. At this time I had already applied to teacher’s college. Now I was in a mad scramble to put together a portfolio, which I had never done before, and complete my application to meet the fast-approaching deadline. I barely passed my pre-interview but was granted permission to formally apply to the BMC program.

New Paragraph

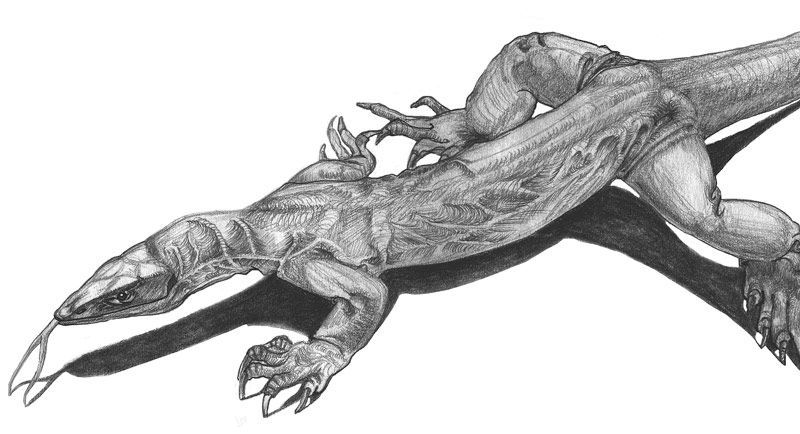

Above: Gould’s Monitor (Varanus gouldii). Pencil illustration created for Celia Godkin’s non-credit natural science illustration course.

Right:

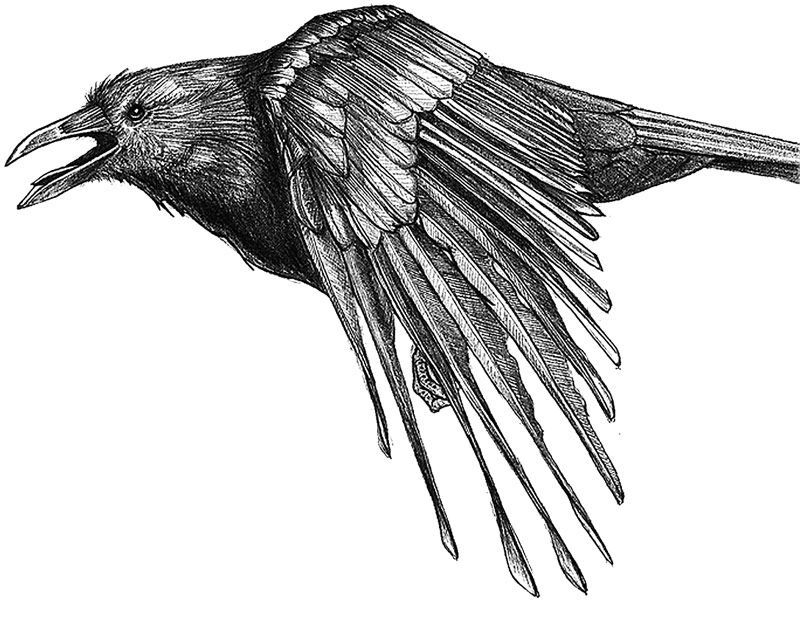

American crow (Corvus brachyrhyncho). Pencil illustration created for Celia Godkin’s non-credit natural science illustration course.

Adjudication was a nerve-racking experience. A table was assigned to each candidate to display their work. Then about a half dozen faculty members, including the late Steve Gilbert*, conducted the interviews and portfolio reviews. I felt completely out of my league and somewhat embarrassed about my work. When adjudication was over, I remember walking towards the subway and thinking to myself, “I guess being a teacher won’t be so bad and I’ll have summers off too” because I had just received admittance into the faculty of education the week before. Shortly after I arrived home I received a call from the BMC director congratulating me on my admittance into the program. I couldn’t believe my ears! I was overjoyed with this news. I contacted the faculty of education to decline my acceptance. I was told they would defer my acceptance for a year; I thought that was ideal because if I didn’t like scientific illustration, at least I had a secure backup. I have never looked back.

I’m so glad I entered the BMC program when I did because, upon entering, I received extensive training in traditional media (e.g.carbon dust, pen and ink, watercolor, scratchboard, continuous tone, stipple, photography and coloured pencil) and cutting-edge digital media (e.g. 3D modeling and animation, web design, interactive media and post-production techniques for video and animation, raster and vector art and desktop publishing). When I entered the BMC program, it granted a 3-year Bachelor of Science degree. The program transitioned after my second year, and I formally entered the graduate BMC program in my third year.

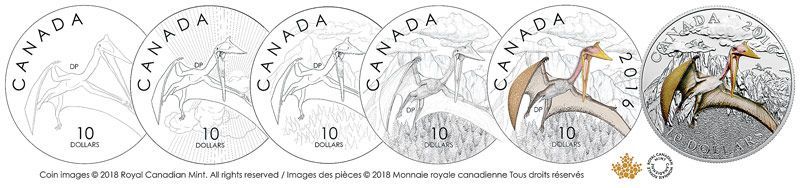

This legal tender collector coin features the largest known animal to fly, the pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus. It is a 1/2 oz. fine silver colored coin in a three-coin series entitled Day of the Dinosaurs: Terror of the Sky.

During my time at BMC, I felt privileged to participate in human dissections, watch surgeries inside the OR, attend an autopsy, watch the birth of triplets and learn many other aspects about the human body. But I quickly realized my true passion was with non-human natural science illustration. This was solidified when I was first introduced to the Guild Handbook of Scientific Illustration and knew I had to have this book. As a student with limited funds, over the next few years I managed to scrimp and save until I had enough money to buy my own copy. It is still one of my most treasured books.

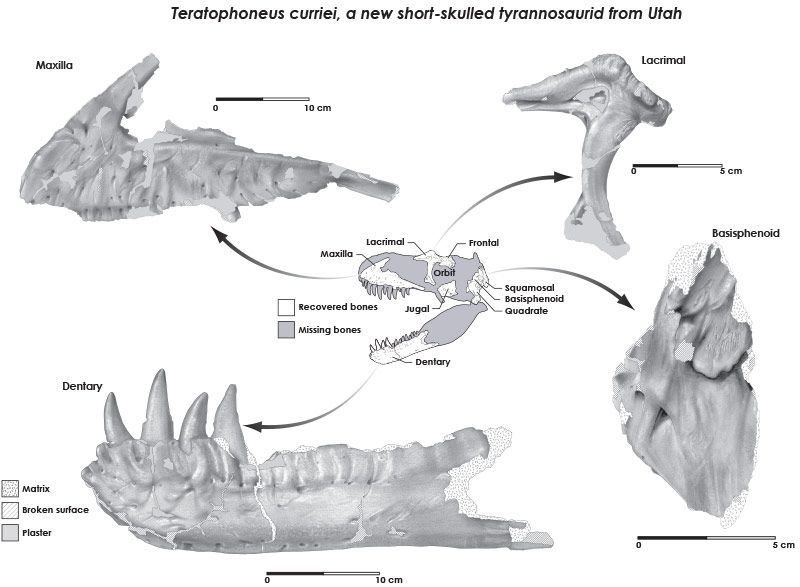

In my first year in the BMC program, we had a self-directed independent project of our choice. I chose to illustrate and compare the skulls of three similar Tyrannosaur species. Unlike most dinophiles, I didn’t get bitten by the dinosaur bug until my early twenties. While working at the ROM on my Tyrannosaur skulls I met a graduate student by the name of Thomas Carr. We immediately hit it off because he was looking for an illustrator to depict his Tyrannosaur research and I was interested in producing paleoart. Thomas is now one of the world’s leading experts on Tyrannosaurs, and we have been working together ever since that fortunate day. We originally produced traditional carbon dust illustrations and are currently using digital media. Thomas recently described a new species of Tyrannosaur,

Daspletosaurus horneri in which I created a life restoration (Journal of Natural Science Illustration. 2017. 49(2):3-6) and later this year he also will be publishing a field guide about the fossils of the Hell Creek Formation of Montana where I created a couple dozen illustrations of reconstructed organisms.

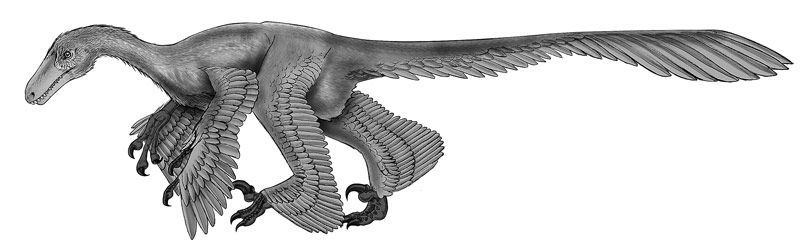

Above: Acheroraptor, a feathered velociraptorine dromaeosaur from the Hell Creek Formation of Montana. Graphite pencil rendered in Photoshop®, published in Carr, T. D., M. Seitz, and D. Pulerà. 2017. Fossils of the Hell Creek Formation: A Carthage Institute of Paleontology Field Guide, Third Edition. Kenosha: Self-published.

Right: Traditional carbon dust illustration of Albertosaurus libratus colourized in Photoshop; created for Thomas Carr and published in Carr, T. D. 1999. Craniofacial ontogeny in the Tyrannosauridae (COELUROSAURIA, DINOSAURIA). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 19 (3):497-520.

Traditional carbon dust illustration created on illustration board and Conté pencils commissioned by Thomas Carr.

After undergrad and before starting BMC, I enrolled in a CVA (comparative vertebrate anatomy) course. That’s when I met Gerardo “Gerry” De Iuliis, who, at the time, was one of the lab teaching assistants. We became instant friends because we had many things in common. For instance, we are first generation Canadians of Italian immigrant parents, we both loved hockey (not surprising from a couple of Canadians, eh!) and we both had a deep interest in paleontology and animal anatomy. During our CVA labs, Gerry noticed that I liked to sketch my dissections. He asked if I’d be interested in volunteering some of my time in illustrating fossils of giant ground sloths for his Ph.D. research.

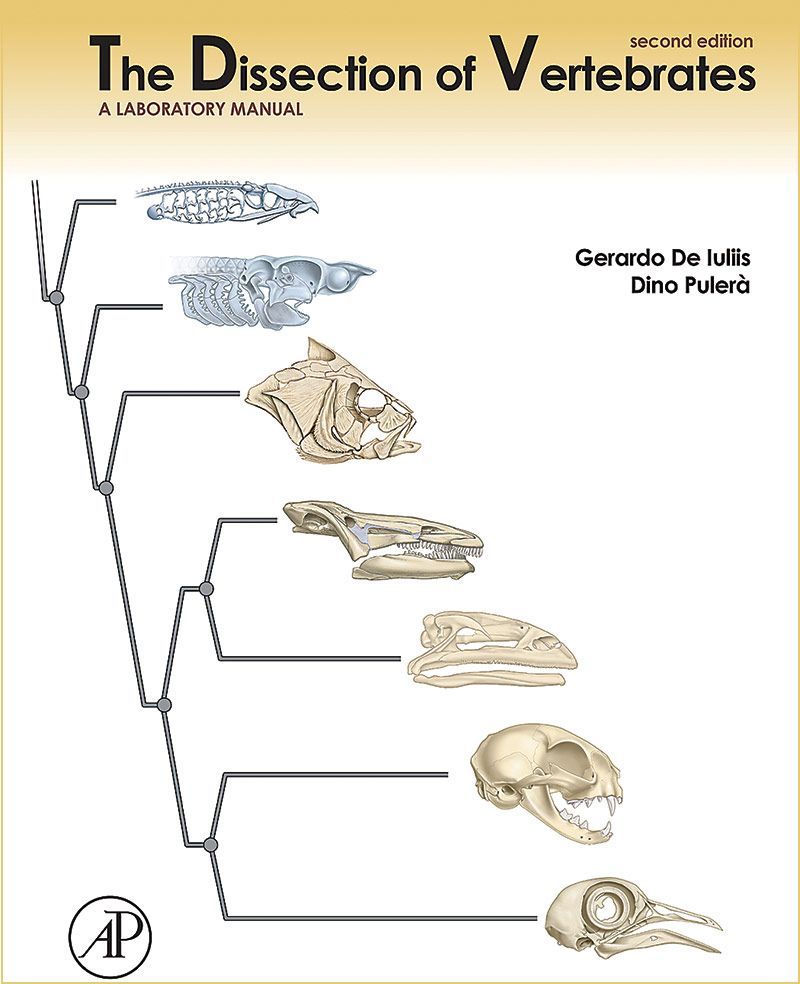

I gladly accepted the challenge. Several years later while working in his office on some fossil sloth illustrations, Gerry lamented that he was frustrated with the available CVA books on the market. These books all tried to be a textbook and lab manual at the same time and this was confusing students as to what they were responsible for in the lab. So he nonchalantly asked me if I’d be interested in teaming up with him to create a new CVA manual. I jumped at the opportunity because it was a professional dream and goal to illustrate a book and earn co-authorship just like my mentor Steve Gilbert*.

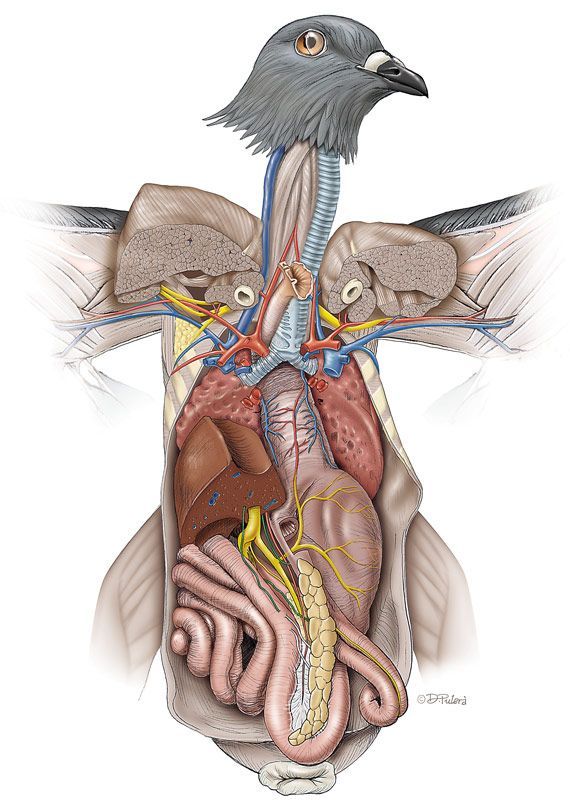

Rock Dove (Columba livia) viscera in ventral view (pencil sketch and color rendering in Photoshop®). © Dino Pulerà. Illustration published in De Iuliis, G and Pulerà, D. 2011. The Dissection of Vertebrates: A Laboratory Manual, Second Edition Amsterdam: Elsevier / Academic Press.

Shortly thereafter, Gerry wrote a proposal and I created some sample illustrations and we started sending our proposal package to various publishers. After more than a year of pitching our book idea, we found an interested publisher and they gave us 18 months to complete the book. We naively thought we could meet this deadline. But after six long and arduous years and two publishers later, we finally completed the book which was published in 2007. Our book celebrated its tenth-anniversary last summer. Since its publication it has received modest success and won several awards, to warrant the publisher’s request for new editions. We are currently working on the third edition with the hopes of a late 2018 or early 2019 publication date.

The second edition cover of The Dissection of Vertebrates: A Laboratory Manual. 2011 De Iuliis, G and Pulerà, D. The Dissection of Vertebrates: A Laboratory Manual, Second Edition. Amsterdam: Elsevier / Academic Press.

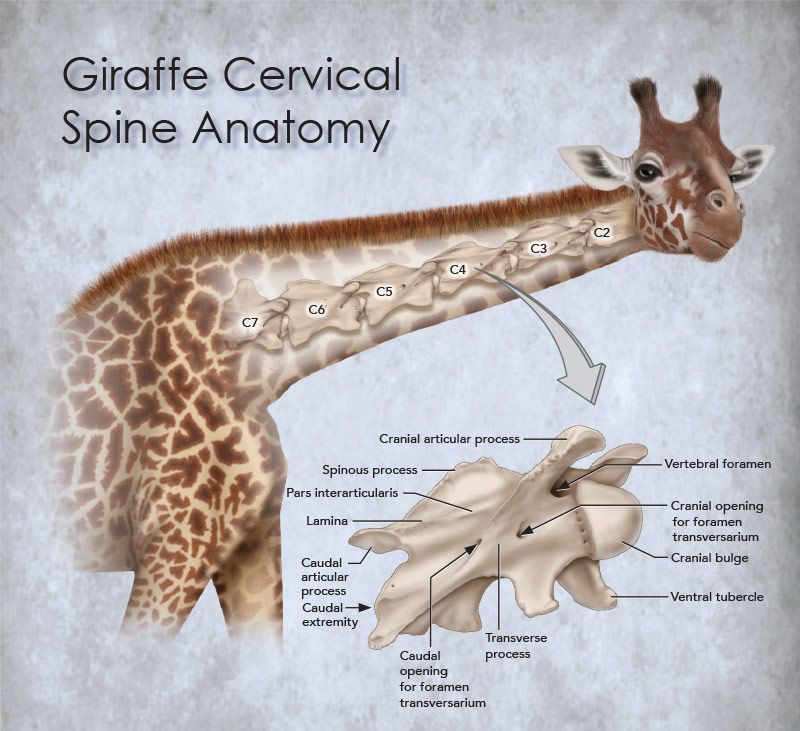

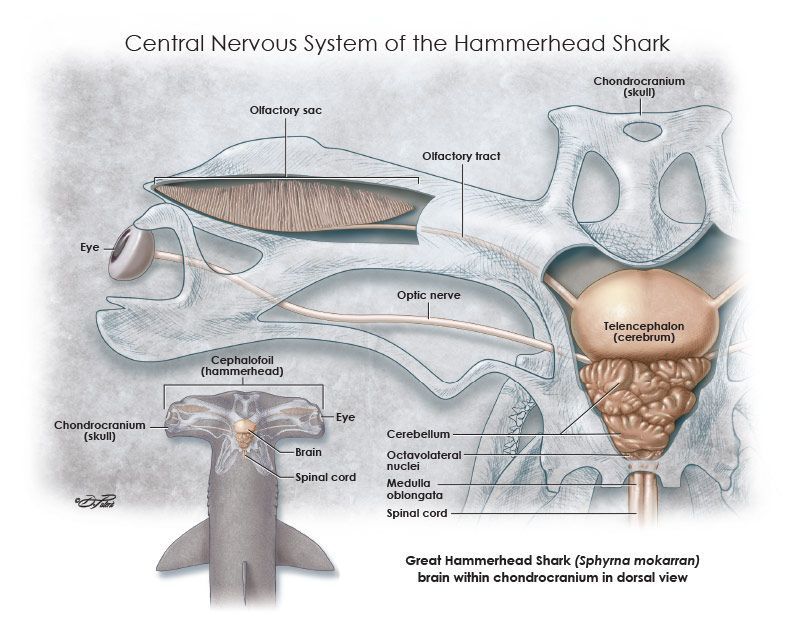

Upon graduating from BMC, I was very fortunate to have been hired by a studio that created textbook illustrations and animations. During this time I contributed to over 70 titles on topics as diverse as genetics, chemistry, geology, human anatomy, physiology, and herpetology. It was a great place for a newbie to learn and grow. I learned to use many types of software from vector to raster to 3D modeling to 2D and 3D animation to desktop publishing. But after seven years I felt that I became stagnant and was getting bored and felt it was time to move on. Once again I was fortunate to have joined another excellent studio specializing in medical-legal visuals. I was hired for an art director position but before I could assume that role I had to learn the ins and outs of the studio and the medical-legal illustration field. I spent the next two years illustrating and rendering trauma, surgery, pathology, and other medical concepts. I currently hold a full-time position at Artery Studios as the associate art director. My freelance work predominately deals with natural science illustration, with a specialization in depicting animal anatomy and vertebrate paleontology.

If you’re interested in knowing more about my career path, here are some online interviews: Science Magazine, SONSI

*The late and great Steve Gilbert was very influential in my career. You can read more about that in an article I wrote in the 2006 Journal of Natural Science Illustration38(8):17-22.

Notes: Images with labels have been modified by the editors for better visibility in this publication. All art © Dino Pulerà

This article appears in the Journal of Natural Science Illustration, Vol. 50, No. 1, 2018,