Interpreting Five Fingers, an interview with Sharon Birzer

– An interview by Audrey Freudenberg with artist Sharon Birzer.

EDITORS’ NOTE:

GNSI member Sharon Birzer asked Audrey Freudenberg for help in writing an article for the Journal. We were intrigued by the story and the nature of its telling. An interview format worked the best. We find that the nature of the telling reflects how the artist-illustrator both grasped the task and was overwhelmed by the subject. It Illustrates the resulting synthesis, and gives some cautionary notes about managing scientists.

AF: Sharon, Five Fingers Lighthouse in Frederick Sound, S.E. Alaska, is by definition, off the beaten track. How did you find yourself there?

SB: The path to Five Fingers—well, I suppose it was a combination of obsession with the impossible and improbable selection: I was trying to learn about whales and ended up being captured by them in a way I hadn’t anticipated. The lighthouse is built on one of five islands in Frederick Sound that were named because they kept catching boats. People thought the islands were the tips of fingers reaching out to grab sailors. So, what brought me and what caught me: in my “fine” artwork, I had been trying to capture the essence of internal systems in two- dimensional images, in a series called Body Interiors (Fig. 1). I printed the ground and silhouettes of human or animal bodies; on that ground I layered very detailed watercolor paintings/illustrations of found objects and symbols—things I found significant to those bodies in a metaphorical sense.

Figure 1: Three images from the Body Interiors series; © 2010 Sharon Birzer

I was working with a combination of literal and metaphorical internal organs; at the time I described it for an exhibition:

“My work investigates and invents systems; internal, external, fictional and actual. Objects culled from my daily life appear in sequences that collectively inquire into the dynamic paths of labor, fruit and waste

that bodies have to offer. The body is the site of our stories. In Body Interiors I take the body as a space for creating narratives, inviting multiple interpretations.”

I was trying to explore the body as a place, a body as a location. Then in one of those brilliant moments when two branches of my multi-disciplinary career intersected, I participated in the GNSI 2012 Education Series Workshop: “Drawing on a Sense of Place” in Pablo, Montana, within the Flathead Indian Reservation. That time with Linda Feltner provided an immersion into the people and environment of the Flathead Reservation. We studied how to interpret the land, people, geography, flora, and fauna of an area. The description of the workshop read “We will discover the breadth of human history and native landscape and explore the means to capture its essence in interpretive illustrations.”

AF: So the workshop, in effect, helped expand your work on “body” and internal systems to include an external place.

SB: In a way it did, yes. Whales are native to Puget Sound and I think of them as part of home; but as I found myself—in their innards?—I realized I knew little about them. I was working on a scientific illustration of Orcinus orca, Killer Whale. This was a composite illustration of the internal anatomy with five layers; the epidermis, the muscles, the bones, and the internal organs with special attention to the echo-location mechanisms and the breathing apparatus. That’s what brought me to Fred Sharpe’s talk at the 2011 GNSI conference in Olympia. Fred gave the keynote speech that year, “Ocean Salubrious;” and I asked him for possible resources for the illustration as I had come to an impasse in my own research.

![Orcinus orca, Killer Whale cranium [mirrored here], ©2015 Sharon Birzer, (with thanks to VZAP for bone scan reference)](https://lirp.cdn-website.com/21596260/dms3rep/multi/opt/FeaturedArtistsProjects-FiveFingers-Fig3-1920w.jpg)

Orcinus orca, Killer Whale cranium [mirrored here], ©2015 Sharon Birzer, (with thanks to VZAP for bone scan reference)

AF: Fred Sharpe was one of the researchers at Five Fingers Lighthouse?

SB: He’s a PhD Research Biologist, and he’s been going up to Five Fingers for a couple of decades, researching humpback whales’ foraging patterns and vocalizations. He’s the link between the Alaska Whale Foundation (AWF) and the Juneau Lighthouse Association (JLA). He’s also an artist—four of his pen-and-ink drawings, Orchids (two), Song Sparrow and Black Turnstone, ended up being used on the interpretive panels we created for Five Fingers Island. He also conceived and wrote the text for all of the panels, with contributions from Andy Szabo, Fred’s colleague at AWF. Fred and Jennifer Klein of JLA had written and received a grant from the State of Alaska to fund both further hydrophone work to record the whale vocalizations and the creation of interpretive panels to become permanent installations on the island, describing the island, its history, its biota, and the role of the humpback whale research being done there.

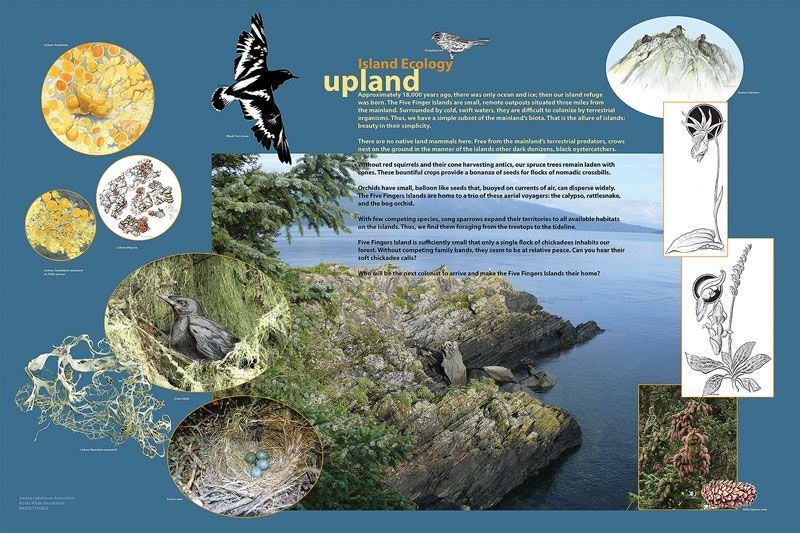

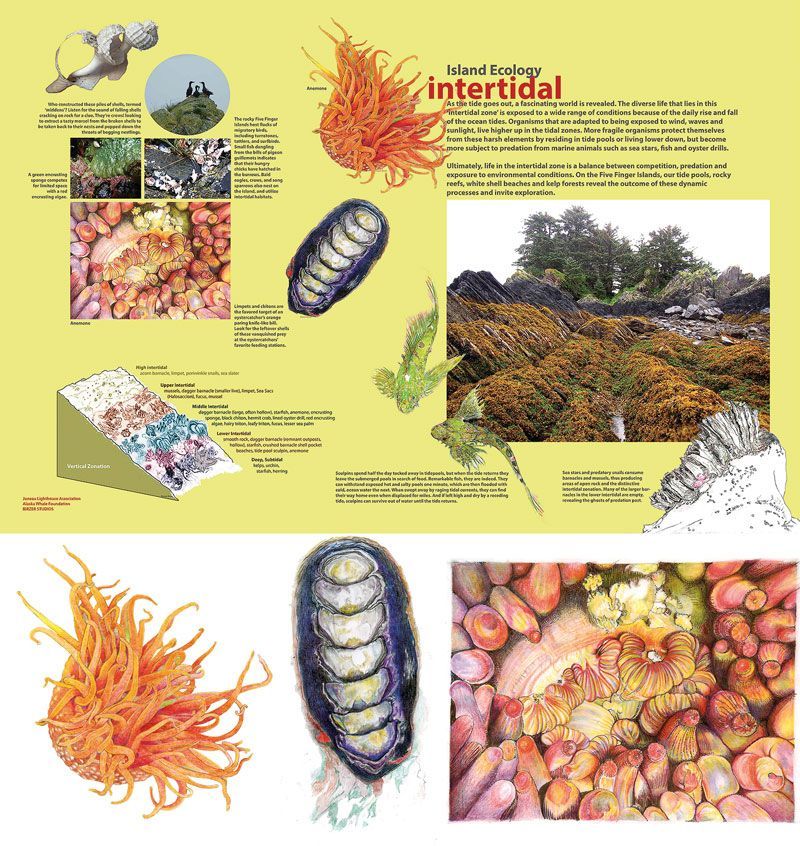

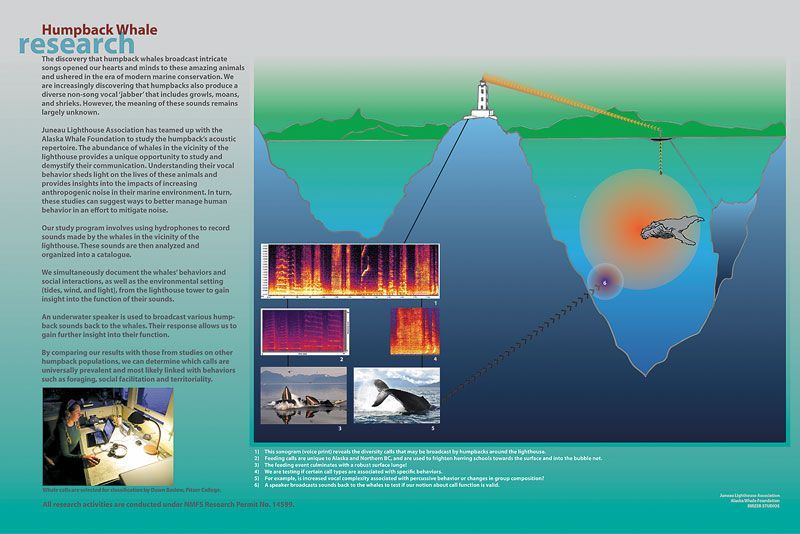

They wanted building names for the five buildings, welcome signs on both ends of the island—there are only really two places to land, the way the rock layers jut out—and we created 6 interpretive panels about the intertidal and upland ecological zones on the island, the history of the lighthouse, the geology of the area and the bigger picture, and two panels about the research being done there (Figs. 5, 6, 7).

The Five Fingers Interpretive Project was to last several years. With the challenges came benefits: my daughter Mallory and I got the opportunity to volunteer on this remote island and watch the researchers at work. I had the chance to explore my interest in whales and learn more about everything there, including the lichens. The hand-done illustrations and photos of the gorgeous life forms, which I created for the panels, including the ocean life and the lichens, ended up being one of the most fascinating parts of the project (Fig. 2).

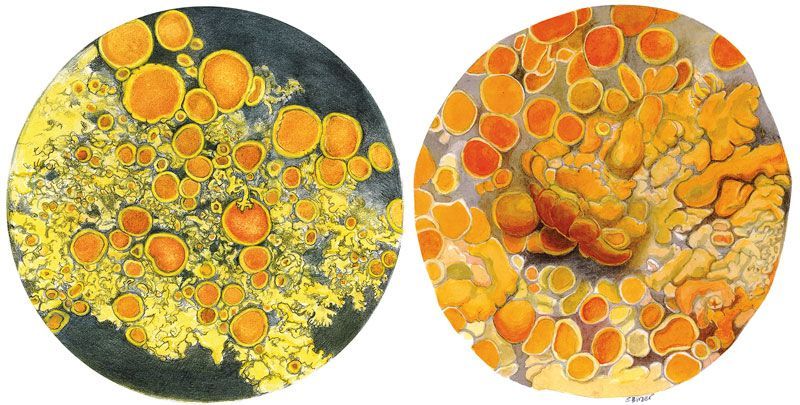

Figure 2: Two species of lichen drawn for interpretive panel (see Fig. 6), ©2015 Sharon Birzer

(left) Candalaria Meneziesii on sitka spruce twig

(right) Xanthoria sp.

AF: Combinations of fungus and algae.

SB: Lichens are bio-indicators, a way to index climate change: which lichens are found in which places tell us what’s happening with the air quality. Karen Dillman, an ecologist and botanist who studies botany, air quality, invasive species and climate change working for the USFS in Petersburg had been contacted and invited to join us to begin a lichen survey. She was kept off the island by six-foot seas, but she later helped corroborated my lichen identification through photographs.

I was in charge of producing the panels. It actually ended up taking a tremendous amount of time, more time than I thought it would. I was the de facto project manager; Fred Sharpe drove the content. The budget I was allotted had to cover not just the fabrication of the images, but everything down to the hardware: these were to be permanent installations on an island that experiences below-zero temperatures much of the year. The printing process alone was expensive and permanent signage is even more so. Then, too, we didn’t want to litter the island! But there are regular visitor stopping points; the geology forces your hand with panel placement.

All images for the panels — both photographic and traditional illustrations — had to start at a really high resolution, at least 600 dpi.

The researchers tended to think that my deadline for the images was their deadline for text; they didn’t fully realize that I was working around their text, so I learned some things about project management! The scientists’ resulting text was really beautiful (“A green encrusting sponge competes for space with a red encrusting algae.”); it was very hard to choose what to feature! There is evidence of life everywhere. Even the trash is interesting: have you heard of middens? Those are the trash-heaps, shells and carapace left mostly by the birds. There are no land predators on the island so I could get fairly close to observe a baby crow and it wasn’t even scared.

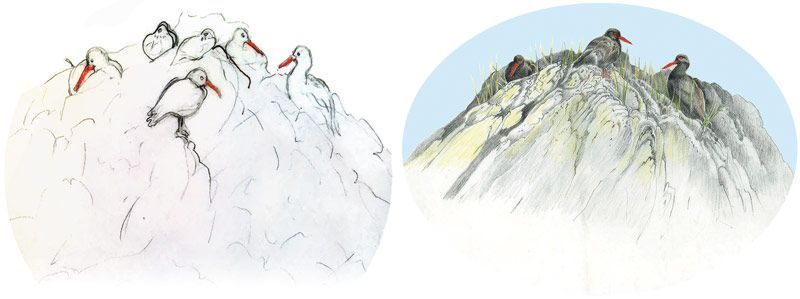

AF: Is that why you chose to illustrate the crow, rather than use the photograph (Fig. 3)?

Figure 3: illustration of baby crow; ©2015 Sharon Birzer.

SB:

I suppose it’s unorthodox to use a sketch (the baby crow) in the middle of a photograph, but the result is somehow softer while being more descriptive. One of the challenges was that the place is so big

and beautiful, and we were trying to create these somewhat educational panels—

AF: Somewhat?

SB:

There was no way we could include everything. And with drawings, you can make the most of the space you have; you can put things together that might not otherwise be; you can call out the defining detail. These Oystercatchers [Fig. 4]: some photographs don’t show that they have almost orange yellow eyes—as bright as their beaks are orange-red. I also just think it’s softer; illustration is slightly digested for the viewer. I used several of my own photographs and field sketches of observations of the Black Oystercatchers to create that illustration. I wanted to put the different views of the animal together, and they were there as a group so I chose my favorite “poses”. It’s possible that strict scientific illustrators frown on this idea—

Figure 4: Black Oystercatcher illustration and sketch (for Upland panel below), ©2015 Sharon Birzer

Figure 5: Upland island ecology panel, ©2015 Juneau Lighthouse Association and Birzer Studios

AF: Like the ongoing debate about the role of the Supreme Court: what is creation, what is interpretation?

SB: We love going to films to see the vision of the filmmaker. I think really hard-line scientific illustrators aren’t supposed to have a style; it’s supposed to look like a clarified photograph. I admire that work, but this job wasn’t just a straight report. We could do some translating. We had to just sample the ecosystem, anyway, as we had no hope of reporting it in its entirety. The interpretive panels were intended to help people connect with and celebrate the place rather than be overwhelmed by it. What we wound up doing with the text and then with the panels was to underscore the experience of the wildlife: the panels teach you to explore, to notice.

AF: Suggesting that you go and discover more than the panels can teach you.

SB: Yes!

AF: I wonder whether illustration doesn’t open a more participatory process than photographs for the viewer? Through mirror neurons people could technically imagine themselves participating in the image creation, imagine their own hands making those marks. A photograph doesn’t give the ordinary layperson a sense of how they might break down three dimensions into two.

SB: I think that’s true. We relied on photographs for overall landscapes, but yes; the drawings were ways we chose to highlight the defining features. Sometimes I think the photographs were more beautiful than the drawings I ended up using— however the drawings could synthesize the important information from several photos into one image.

AF: and the photographs wouldn’t have given the viewer the same whiff of the translational experience.

Figure 6: (top) Intertidal island ecology panel, ©2015 Juneau Lighthouse Association and Birzer Studios

Individual images: (bottom) ©2015 Sharon Birzer:

Left: Metridium senile (Short Plumose Anemone)

Middle: Katharina tunicata (Black Katy Chiton)

Right: Urticina coriacea (Rose Anemone)

SB: Right. We get to learn about these species, and then we discern what information is going to clarify that species for the viewer, distinguish one from the other. Sometimes with the lichens you know you can’t achieve this! It’s an impossible job; but as we learn about the species we pull out the information that’s key. Take some of these smaller creatures: if you just took a giant spotlight you wouldn’t see the form anymore; you’d have flattened color. But I think you could say that we were going for an artist’s view versus a highly technical illustrator’s view. Just as knowing and understanding exist on a continuum so does science illustration. Fred and Jen were allowing me to interpret. It was a dream project, really. It was almost as though, if you could be a butterfly, what would you see if you landed?

AF: So that if a person were, themselves, able to zoom in and out on a sample, or get a different view under bright light, they could refer to your sketches to distinguish features.

SB: Right, exactly. And I got to take lichen samples home; those 18 days were just not enough time to get all the relevant information to get the drawings done.

AF: It’s the little things.

SB: But the big things: the whales? Those researchers have identified and named close to a thousand humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae), based on the different markings on their flukes. The whales come into Frederick Sound after little things, I guess—that’s what the Oceanography panel ended up describing; the upwellings and currents combined with the ice-age geology that carved the sound into a place where, helped by the forces of nature, the krill and fish collect in abundance. The panels about the Oceanography and the Research, though—those were based on Fred Sharpe’s schematics. I interpreted his diagrams and translated them into a tableau in Adobe illustrator, adding clarifying images (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: Humpback whale research panel ©2015 Juneau Lighthouse Association and Birzer Studios

AF: You made six panels altogether?

SB: There are six interpretive panels including the Upland and Intertidal Zones of the island. The Upland area—so named because Five Fingers is uplifted granite from the ice age, all these layers jutting up and out. The upper part of the rock is habitat for plants and birds. Then there’s this broad band of steep rock covered in seaweed and the life you’d normally associate with tide pools: the Intertidal Zone. It’s often in various stages of being covered and uncovered by water as water levels fluctuate with the tides. Fred, myself, and, on a couple of occasions, volunteers photographed plants and animals I ended up illustrating.

AF: You did some of the drawings from life, and some from photographs you took home?

SB: Photographs and field sketches were the basis of the illustrative portion of the work. But the lichens I had to look at through a dissecting ‘scope. I could only see one area at a time; I didn’t get the full view that you see on the panel. The depth in Xanthoria [Fig. 2]—that is like a moonscape; maybe I didn’t do it justice because I didn’t want to put too much shadow in it. It doesn’t show up like this on any camera or dissecting scope that I have: I had to focus back and forth as I drew and painted—focused down into valleys. I did kind of flatten it so you can see it better.

AF: You had to make parts into a whole.

SB: That was the composition challenge for the whole project: to make all the panels look like part of a whole, whether they were about systems or populations.

AF: It feels like an odd time to ask you about beginnings, but how did you approach those design decisions?

SB: I know, I kept getting distracted by individual organisms and details, then as now! We started with biological surveys. I followed Fred Sharpe around the island during his surveys, taking notes and taking pictures. He knows how to identify all the species.

AF: You credited him with some of the inset illustrations on the panels.

SB: Yes; I edited images of the Calypso and Rattlesnake Orchids done by Fred, to get them to high resolution; also the lovely Black Turnstone and the Song Sparrow, all on the Upland panel. Fred’s illustrations and writing can be seen in the books Birding in the San Juan Islands and Wild Plants of the San Juan Islands.

AF: And, of course, birds make up the chief vertebrates on the island—as you said, no land predators. Or should I say, the chief vertebrates except for humans?

SB: I was fascinated by the role of the researchers. You know, I found this mystifying even as I put it on the panels, but the researchers have begun to play back to the whales some of the vocalizations they collected in the past. They are observing the whales to see if they can measure any response to these recordings.

AF: I would think that might be confusing to the whales. ‘Wait, that’s Viking Petal’s voice, but Viking Petal is right here, making no noise. What’s up?’

SB: Again, the trick seems to be trying to isolate part of the animals’ experience; but it seems complex and mystifying.

AF: Trying to foster a sense of an experience rather than pretending to reproduce it in its entirety.

SB: Yes; it’s a long way to go.

AF: Do you want to go back?

SB: I’d love to go up there again. I hope to go to see the interpretive panels and signage work installed on the Island. We actually did get to continue the work at the Center for Coastal Research on Baranoff Island, my daughter Mallory and I, in the summer of 2015. That is when we worked with AWF and Robert Szucs who produced the bathymetry for us.

AF: One experience leads to the next.

SB:

It’s a continuum. Part of the work was funded under the Scenic Marine Byways Grant which had been awarded to Jennifer and Fred, Juneau Lighthouse Association by the State of Alaska. I also want to recognize Fred Sharpe, Andy Szabo, and Robert Szucs and generous volunteers for their contributions of text, photography, reference materials and bathymetry maps. Like I said, a dream project.

Photo of Sharon working, ©Fred Sharpe

Interpretive panel design, illustration and photography by Sharon Birzer at Birzer Studios. Photos, text, and black and white illustrations (Orchids, Song Sparrow and Black Turnstone) by Fred Sharpe. Text by Andy Szabo at Alaska Whale Foundation. Bathymetry by Robert Szucs/Alaska Whale Foundation. Additional assistance by Jennifer Klein of Juneau Lighthouse Association.

The panels are viewable online at:

Share this post: