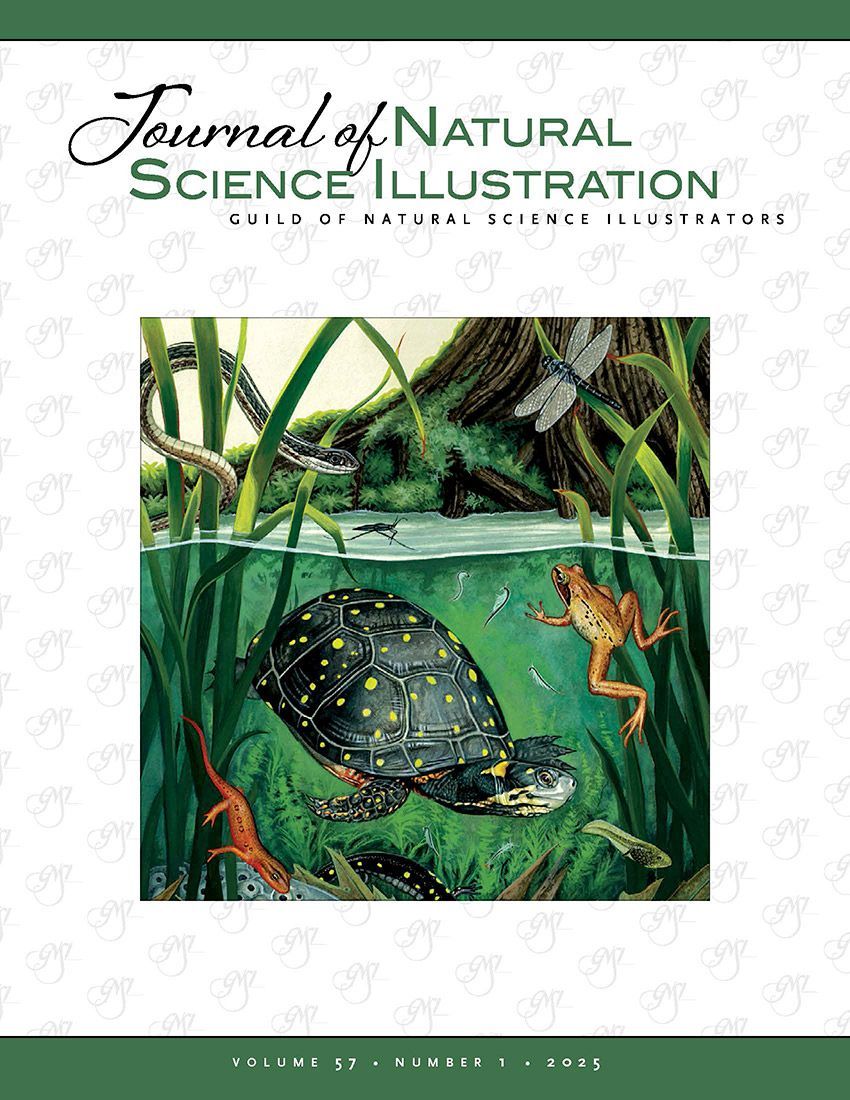

Book Review: Drawing for Scientific Illustrations: Technique and Rendering

I first learned this book was in the making from Lana Koepke Johnson and Jeanette O’Hare while we were on a field trip bus in Queensland, Australia, as part of the 2019 GNSI Conference. Lana explained how she had possession of the scientific illustration class archives given to her by the family of Donald B. Sayner after he passed away in 2004. She and Jeanette have been working on pulling together a book to document and commemorate that amazing class we all had taken.

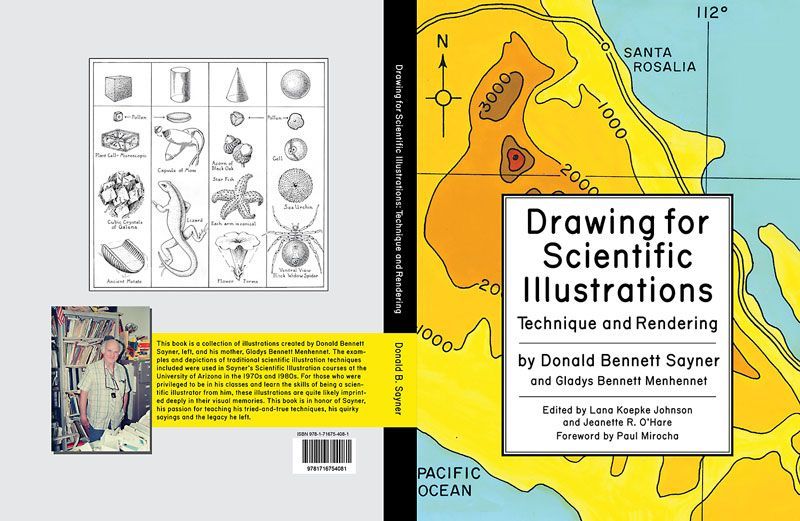

Figure 1: Drawing for Scientific Illustrations: Technique and Rendering - book cover

I was so excited to hear this, having treasured my time in Sayner’s very popular class at the University of Arizona which was my privilege to take (1979–80). I was a graduate student in entomology there; the class was originally designed for students like me—to help in developing illustrations, maps, and charts for theses, dissertations, and journal articles.

Lana and Jeanette had been in another category of students who heard about Sayner’s classes from afar and sought him out from Nebraska to enroll. Lana ended up teaching scientific illustration at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln and based her early course on much of what she learned in Tucson. Likewise, Paul Mirocha, who wrote the book’s foreword, made a pilgrimage from Minnesota to Tucson just to take his classes. As many in GNSI know, Paul became an accomplished freelance natural science illustrator. He remained close friends with Sayner over the years and helped preserve class materials after Sayner’s passing. In the 35 years that Sayner spent teaching at the University of Arizona, thousands of students had taken his classes, many of whom went on to careers in a variety of scientific disciplines. Some became professional illustrators or specialized in some aspect of science communications.

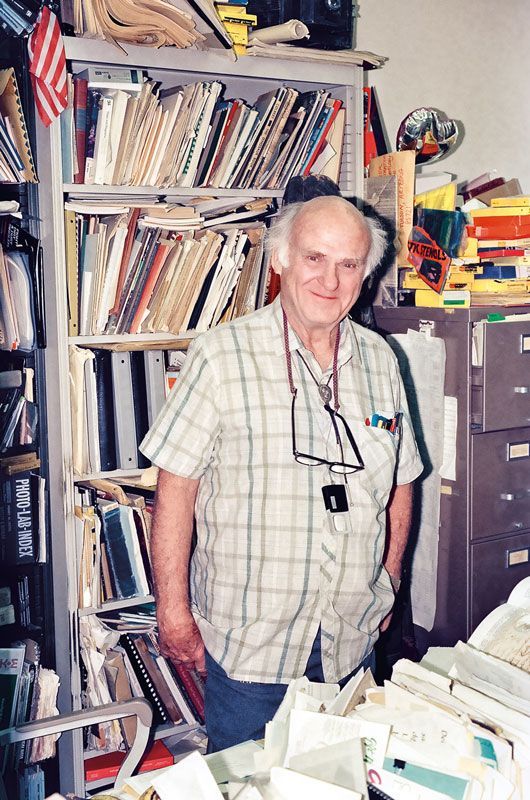

John Sayner in his office. Photo by Lana Koepke Johnson, 1986.

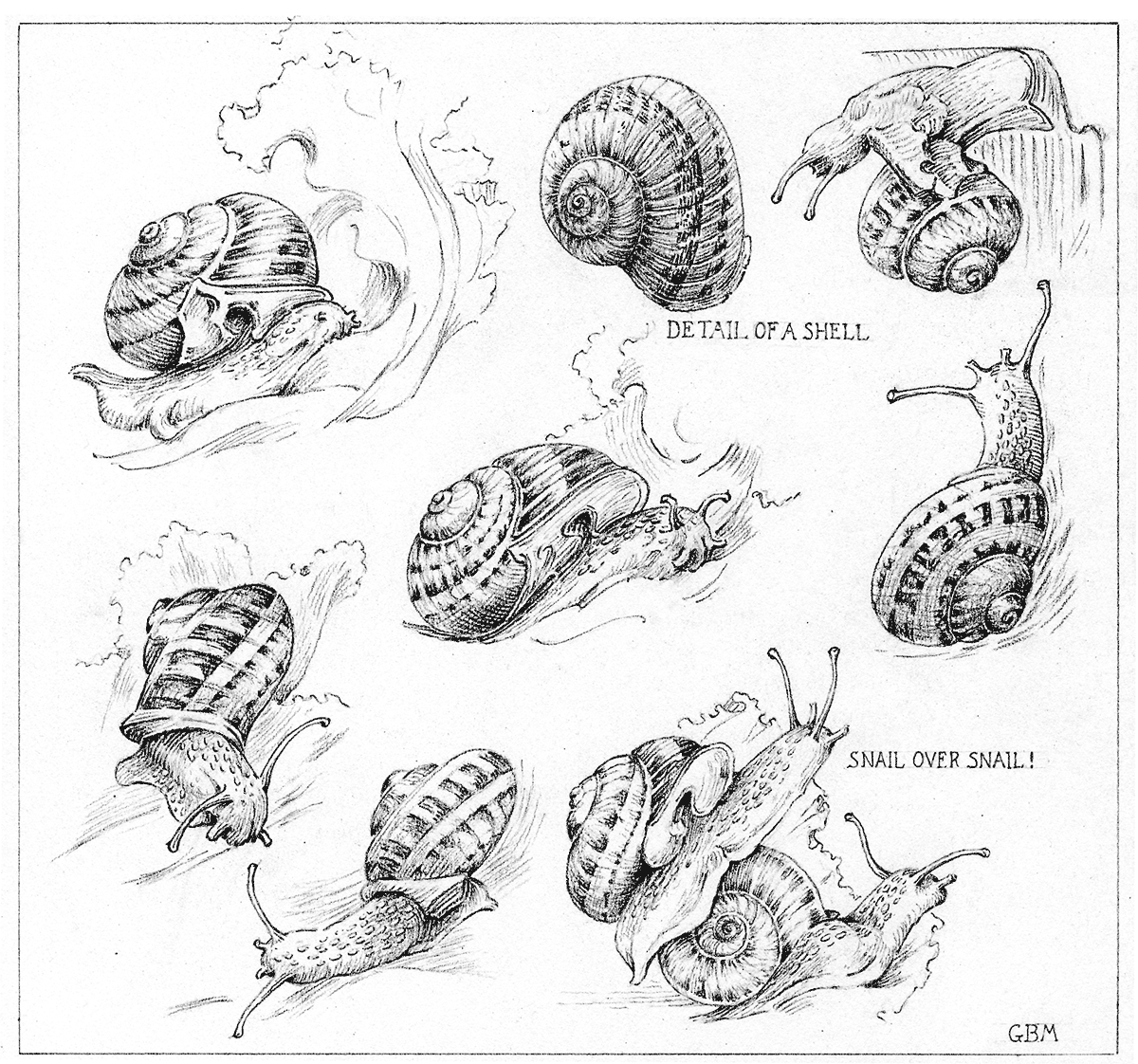

As the book details in the introduction, and in engaging essays by former student and science writer Jill Carpenter (aka Jillyn Smith), Don Sayner (or just “Sayner” as everyone called him) was a special and beloved human being. The book is a kind of time capsule and tribute to the man who used his wit, experience, caring, and dedication to teaching the craft to his interested students. His lectures were full of information, with instructional technique handouts with illustrations done by Sayner, his artist mother, Gladys Bennett Menhennet, or class assistants. These form the main content of the book.

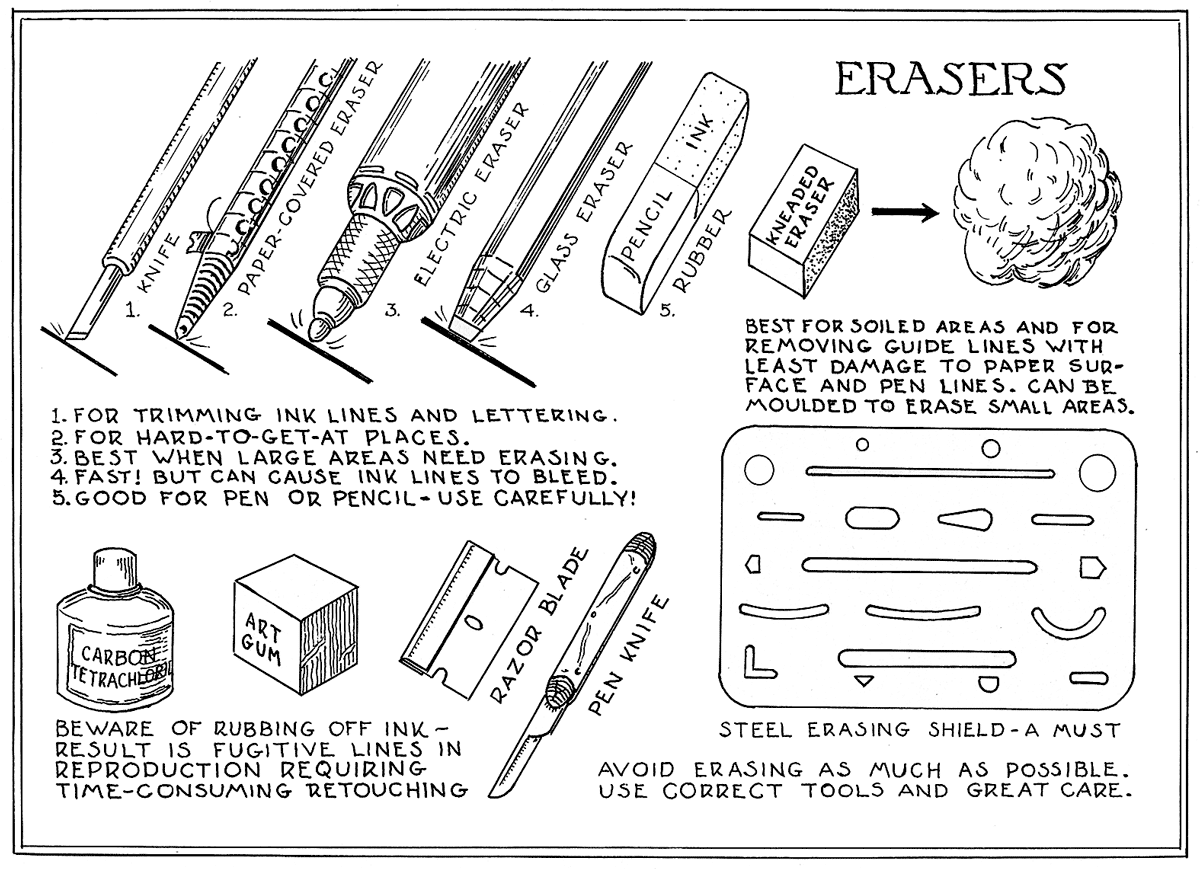

Figure 2: Image from the book about erasers.

In class, his delivery was rather quiet and understated, yet full of expressive surprises, eyebrow raises, and askance looks interspersed with jokes, anecdotes, and dozens of his little sayings, many of which are included in the book thanks to Lana’s great note-taking during class.

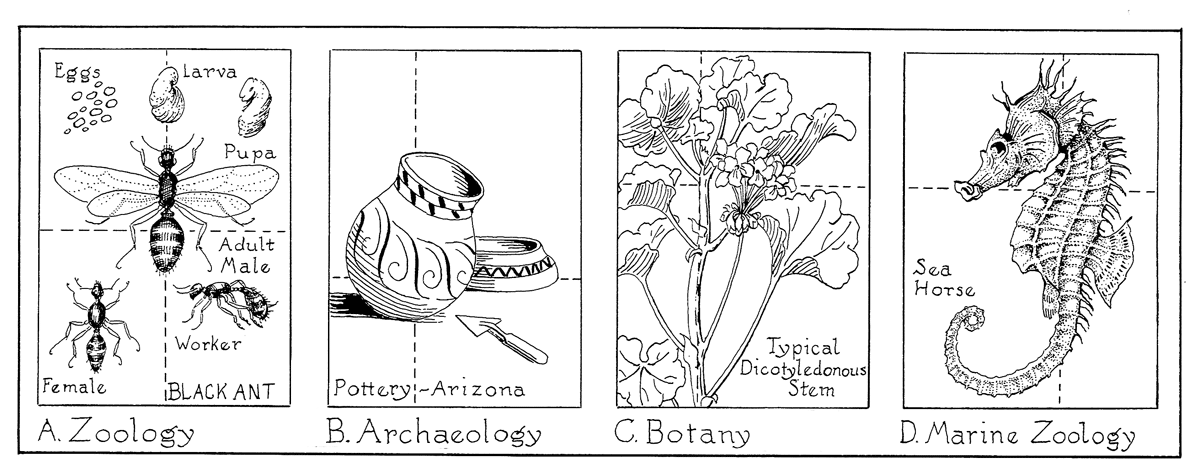

Figure 3: Image from the book.

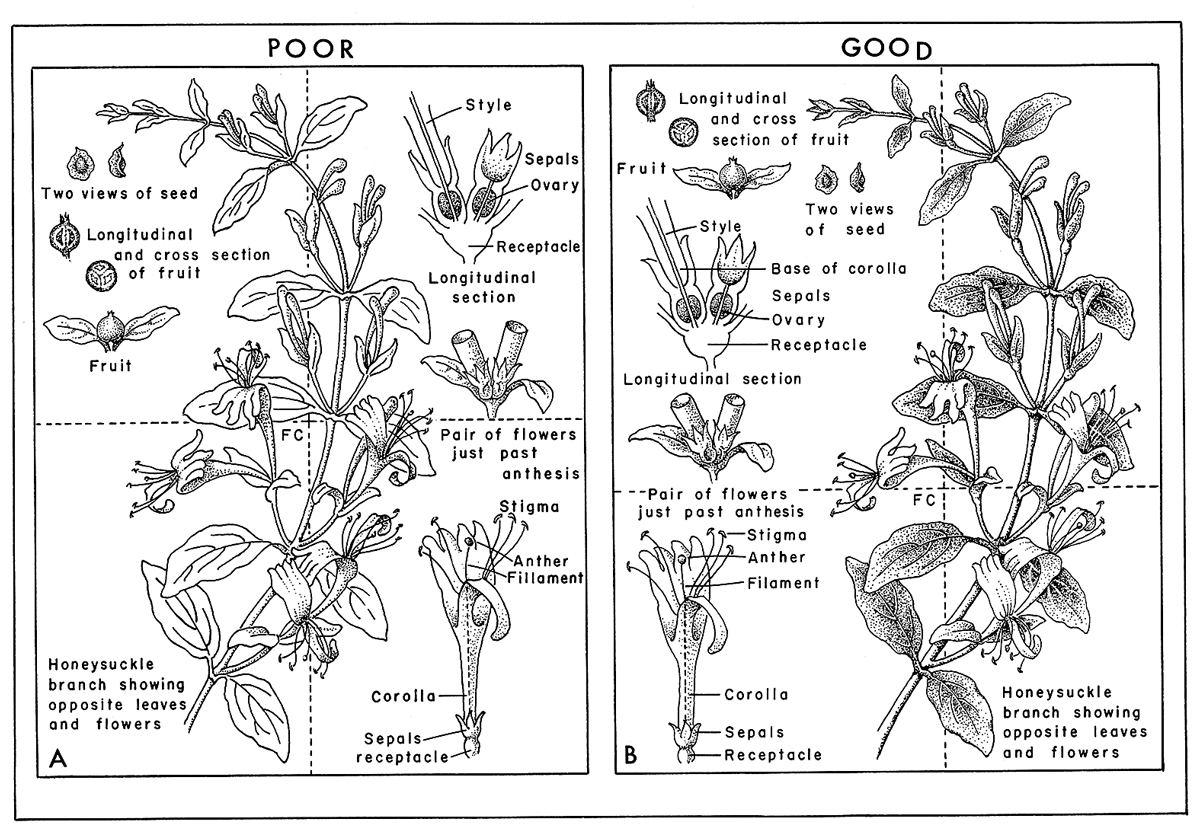

He was very practical in his approach, encouraging improvising with the materials at hand, making adjustments for field conditions, but always demanding excellence in striving for accurate and clear illustration and communication of concepts.

While the time period of the class offerings was years ago, the information in the book is classic and highly relevant. The emphasis is on basic rendering skills, the use of traditional tools, and tricks of the trade to produce a good quality illustration that is reproducible in print. Chapter topics include: knowing your tools, drawing techniques, drawing in perspective, shading, sketching animals, drawing maps, and graphic arts photography.

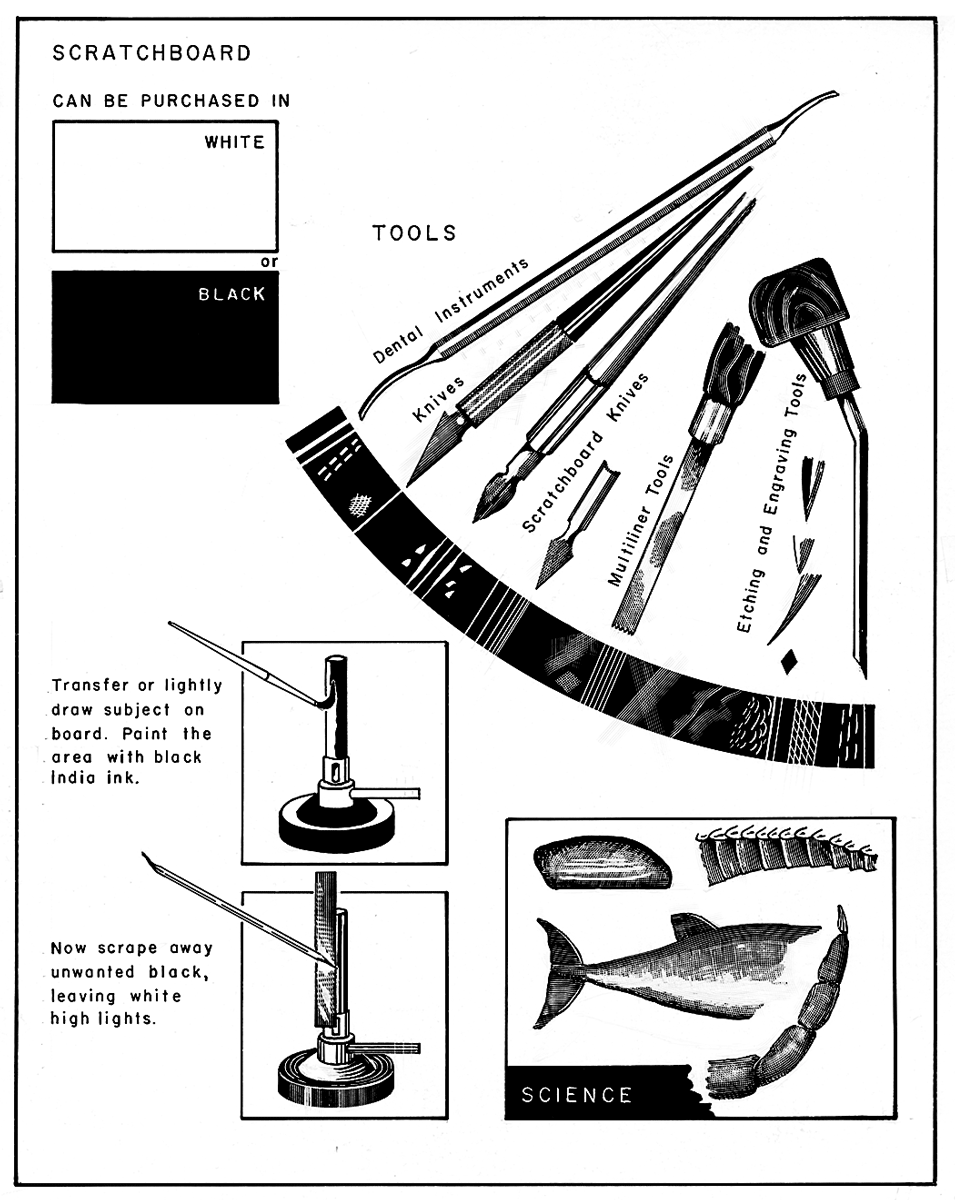

Figure 4: Image from the book. Scratchboard tools & technique.

Sayner was near retirement just as computer graphics were becoming possible and more widely used. The techniques in the book are all traditional; thus the book’s tongue-in-cheek subtitle. As we know, mastery of traditional techniques form the basis for good digital illustration skills. Learning observational techniques, how best to draw with various ink pens, graphite, and how to paint with brushes are well covered along with a variety of other required skills.

While some of the methods documented in this book may become lost arts, they form the basis for how digital tools were developed and often named. For example, one of the most valuable topics of Sayner’s class for me was how illustrations were captured on graphic arts film with a copy camera to produce printing plates for use on an offset printer we used in the classroom. Understanding these basic processes, nicely displayed in the book, helped me later better understand printing specification options required in Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator.

Figure 5: Drawing from his book showing the best practice for botanical layout.

Anyone who took the courses will recognize the map of Baja California, Mexico on the book cover. This was one of the required exercises executed in pen-and-ink with ruling pens, triangles, a T-square, a mechanical Leroy lettering template, and something called a railroad pen for making parallel lines. It is two ruling pen heads on a swivel that takes some practice to use properly for drawing rail lines on maps. The book has a photograph of a railroad pen after the title page with a dedication to Sayner, his students, and the pen. I still have mine.

GNSI owes a debt of gratitude to Don Sayner for his legacy. His courses were one of the few options at the time for those of us seeking to learn natural science illustration practices. I first learned about GNSI from taking Sayner’s classes. Appropriately he was honored at the 1995 GNSI Conference in Flagstaff, Arizona. Many of his former students attended and he was touched by the recognition at the banquet by our group. This book further honors him posthumously, and is a testament to his contributions.

It is fortunate that a few dedicated former students did the work to make a book of his valuable teachings, something Sayner never had time to pull off himself.

Figure 6: Snails by Gladys Bennet Menhennett.

Order your copy at https://bit.ly/2JLLMmZ

Proceeds benefit the Guild of Natural Science Illustrators Donald B. Sayner student scholarship fund: https://gnsi.org/donate.

Figure 7: Railroad pen

Share this post: