Member Spotlight: Amelia Janes

– All Artwork © Amelia Janes

Abstraction: Artwork that reshapes the natural world for expressive purposes may be called abstract. Art that derives from, but does not depict, a subject is abstraction.

For me, the study of art and abstraction came hand in hand. I spent the late ‘70s in art school in western Kentucky trying to bend reality in paintings and drawings. At the time, I thought all fine artists must “abstract”. I believed that the act of abstraction should be the main subject matter for contemporary artists, more than whatever object or situation sparked the impulse to make the drawing or painting in the first place. Eventually, as I worked on a masters in fine arts (MFA) in Wisconsin (Madison), I came to understand how much the natural world influenced me. Everything I made, no matter how abstruse or referential, was really a method of illustrating something I observed or I learned about my environment.

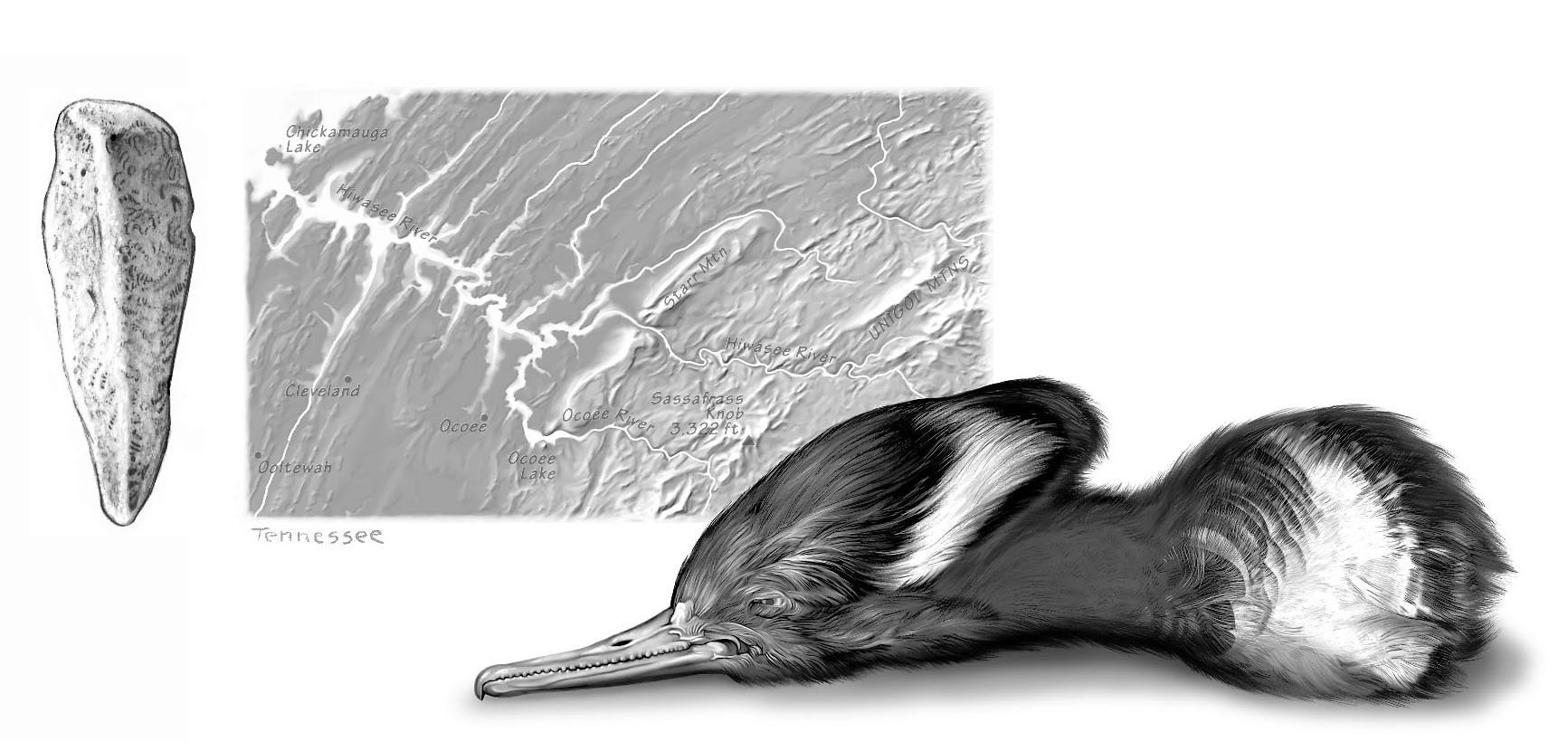

I suppose this revelation — that illustrating the natural world would be prominent in my artwork — links to a rural upbringing. My favorite place to be was my great-aunt and -uncle’s farm outside Chattanooga, Tennessee. Jack and Sis bought the farm in the 1940s, near a town called Ooltewah (great name, eh?), cleared fields and built their home on a rise overlooking the orchard and the Appalachian foothills. They loved to hunt, fish, camp, and hike in parts of Tennessee and Georgia that are now national parks and state recreational areas. Both my aunt and uncle knew a great deal about plants and animals. My uncle grew crops and raised livestock to feed his family and to sell to local markets. My aunt took my siblings and I on long hikes identifying wild plants. She was passionate about wild flowers and cultivated many specimens in her garden. She especially loved the native orchids, lady slippers and twayblades. We would get up early on a summer morning, and follow my uncle on his rounds in our pajamas, feeding chickens and turkeys, pigs and cows, and the jumble of beagles and mixed breed hunting dogs. I thought of their farm as home in many ways, as my family tended to move every four to five years. We spent part of our summer there every year.

Merganser head, Native American stone celt and map, 2006.

I loved to browse through my great-aunt’s set of Golden Nature Guides. I still have her well-used collection of little books, spines broken and pages earmarked on the critters and varmints that we all saw on the farm and the wooded areas we explored. I loved how the illustrations showed so many aspects of a particular subject matter, from the beauty of the wing markings of butterflies to range maps to vignettes of feeding and breeding behavior. My siblings and I would roam the farm in the mornings, looking for frogs and fishing for pan fish in the surrounding ponds, looking for cats in the hay loft, and musing about the Civil War era tomb stones in the graveyard tucked in the woods. We’d spend the afternoons reading and browsing through field guides and stacks of National Geographic magazines.

As an art student in Kentucky, I followed the art of Dorothea Rockburne. Dorothea studied at Black Mountain College in North Carolina in the 1950s — the avant-garde experimental art school based on John Dewey’s principals of education. Joseph and Anni Albers came to teach at Black Mountain College after leaving Germany, located near Asheville, NC. When I first encountered Dorothea’s work, I pursued a fascination with minimalism. At first glance, her work seems to fall under the minimalist movement umbrella. As I looked more at her constructions, I began to see her work as an expression of processes of the natural world. She inspired me to think how I might express my understanding of my environment through visual art. And what wonderful coincidence that my husband and I eventually moved to the town of Black Mountain not far from Lake Eden where the college once held classes! I met Dorothea Rockburne in the 70s after finishing my BFA. She is known for welcoming artists and students into her studio, and she was very kind to me. I met her again years later at the opening of an exhibit of her work held in the Black Mountain Museum and Arts Center in Asheville. She was the keynote speaker for their annual conference.

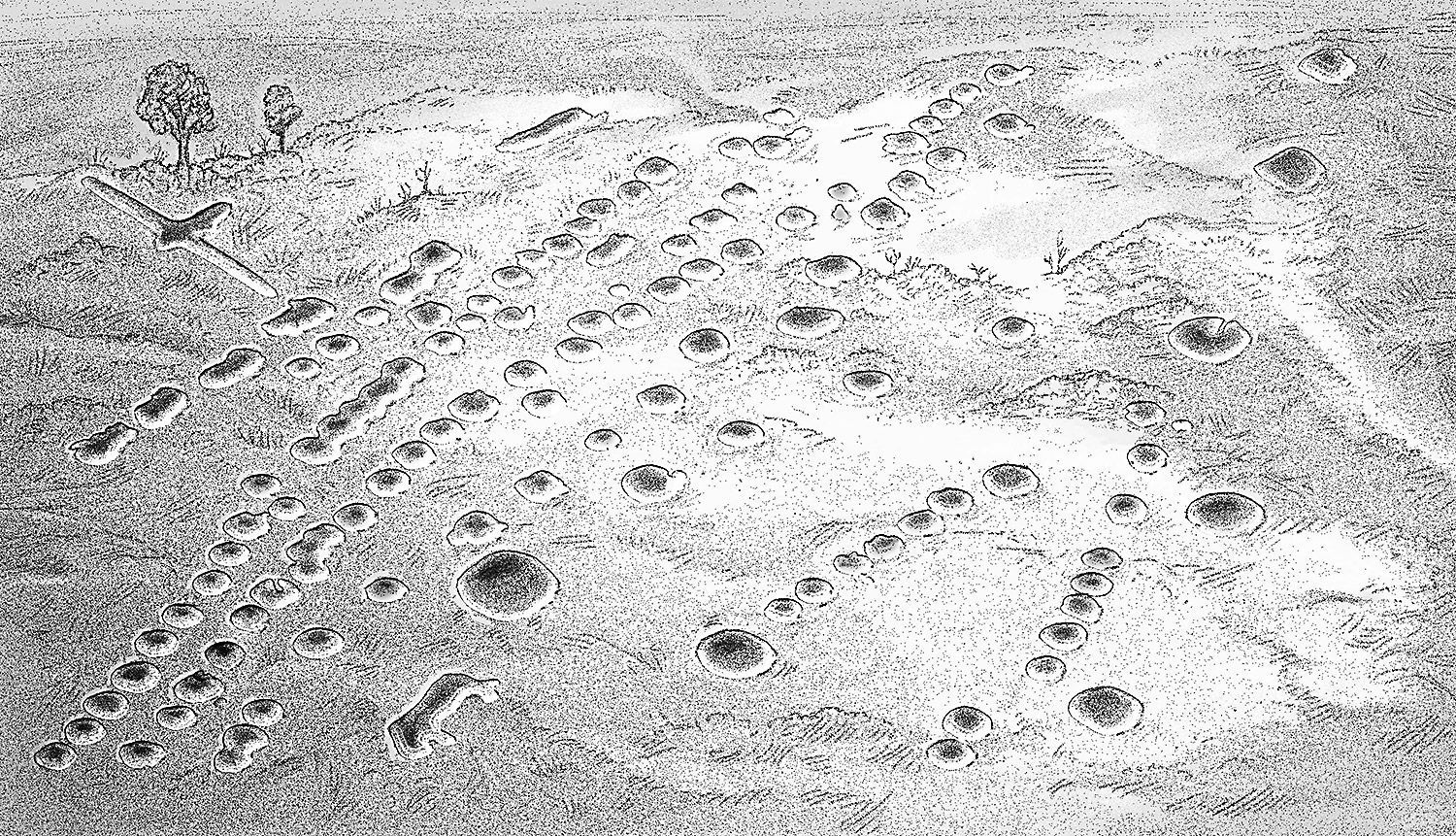

After completing my MFA in Wisconsin, I Iooked for ways to connect my rendering skills with a scientific study. Wisconsin has the largest number of Native American effigy mounds in the US, and I studied and observed their history and physical presence. Effigy mounds are not always very grand, sometimes they just look like low broad piles of dirt, usually in places inconvenient to modern developers (but probably meaningful locations at the time they were constructed). I joined a surveying team from the university, camping out in central Wisconsin, surveying a very large group of effigy mounds, plotting their shapes and collecting data. I began to think how my interpretive and rendering skills could be used to do more than simply illustrate my state of mind, and instead be driven by collaboration with others studying the natural world and archeology.

Untitled oil painting, 1976.

This experience led me to pursuing cartography as a profession. The University of Wisconsin has an outstanding cartography program, and after finishing my MFA, I found myself hip deep in mapmakers. I loved the way that maps are like an abstraction of the landscape. My cartographer colleagues and I were working on maps before computers became the main tool of production. I would spend my working day cutting through emulsion with sapphire tipped scribers, cutting rubylith, burnishing type on acetate, and compiling layers of components for the darkroom.

Eventually, I began to study and practice shaded relief techniques, the art of interpreting contours to create terrain. Even though computers were starting to be used for some aspects of cartographic production in the late 1980s, shaded relief was still done as layers of compiled data with graphite, color pencils, velum and sometimes airbrush. I scrounged in old army manuals to teach myself the effects of light source, and aerial perspective.

My growing involvement with GNSI played a large role in developing my carbon dust techniques, which I applied directly to my shaded relief. Taking workshops with Elaine Hodges, I learned how to trim and singe sable brushes to customize their shapes. This form of “dry” tonal painting brought together many aspects of my art school training, my desire to use my rendering skills for commercial purposes, and my skills of interpretation.

Of course, computers came on the scene and started changing everything, which was true for all kinds of pursuits — business and networking as well as making maps and illustrations, so back to the drawing board to learn a totally new tool. I continue today to use the computer to compose, draw, paint, shade and model. GNSI colleagues and workshops continue to support my art and illustration pursuits.

My husband says I often add life, style or emotion to factual material; adding aesthetics to informational graphics best demonstrates all that I have learned.

Cranberry Creek Mound Group, Cranberry Creek Archaeological District, Necedah, Wisconsin, 1985.

Share this post: